Is there a more confident, polished, completely self-satisfied city than Bern, Switzerland?

It’s not just that it’s the “Federal City” (please don’t say “capital”) of a famously wealthy and orderly country, the meeting point among its French, Italian, and German identities. It’s not just the long history of sovereignty, not just as a city but over a vast canton reaching to the summits of the “Bernese Alps”. It’s not just the fresh, cold water falling into pools all over the old town.

It’s that nothing about it seems accidental, as some aspect of most cities does. Everywhere I looked I saw design, intention, control.

So when a frequent trolleybus takes me past cornfields, I know someone intended this.

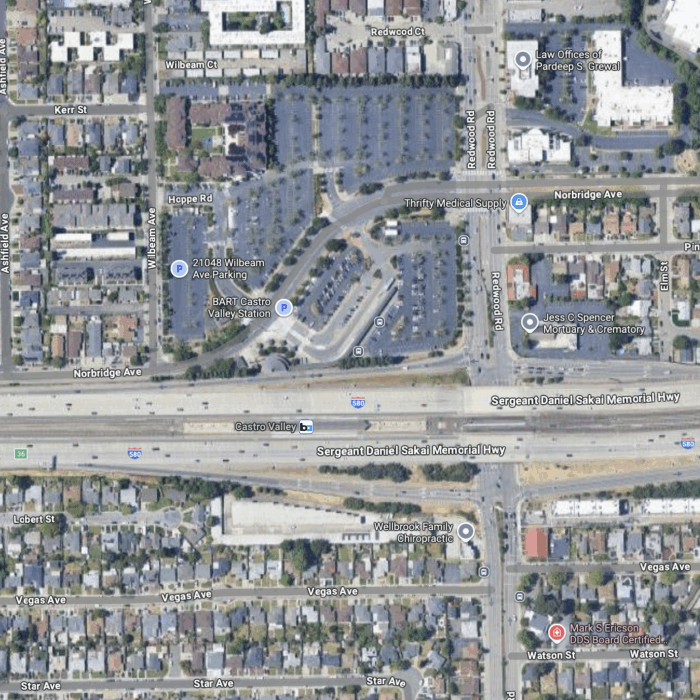

I noticed this odd shape of Bern first when we climbed its highest hill, the Gurten, and looked down:

Many well-planned European cities have hard edges, with ten-story buildings looking directly out on farms, but it’s not as common to see farmland so completely surrounded by the city, so that urban infrastructure, such as frequent public transport, will waste some of its capacity serving a place with no demand.

But the frequency! While we were at a cafe in the old city I kept wanting to photograph how incredibly often the trolleybuses were coming by. One seemed to always be at the stop. But of course, you can’t photograph frequency, and all I got was photos of a very nice bus.

Switzerland, like much 0f Europe, is very sentimental about agriculture. Around the Paul Klee Center, a major museum devoted to the early 20th century painter, still more expensive urban land was devoted to corn, with an interpretive sign of course.

But every city sets aside land for some ceremonial purpose, so if agriculture is what people want to see from their frequent buses, it’s what they should have. Even the old city has steep terraced slopes that have been gardens for centuries:

If you are anywhere near, I do recommend Bern, a walkable historic city on a dramatically fast-moving river. If you need transport things to do, there are funiculars, sleek modern trams, and abundant trolleybuses. For true access geeks, there’s also the half-hourly event at the rail station when trains in all directions are there at once and leave within a few minutes of each other, an aspect of the famous “clockwork” nationwide rail schedule.

And don’t miss the opportunity to notice how similar they want the trams and buses to feel, so that you don’t develop attachments to technologies but just use whatever goes where you’re going.

But then, just walk. Indeed, if you walk far enough, a pleasant city street may turn into a Wanderweg, the network of hiking trails that laces the whole country, which are so popular that you may find a little shop selling coffee or cheese by the path far from any road. These trails, too, are part of the romance of agriculture. While I was there, someone on Twitter was going on about how poor Europe is and mentioned that it has nothing like American national parks. Yes, Europe has long been so thickly settled and cultivated that has few wild areas on the scale of Yosemite or Yellowstone. What it has instead are hiking trails everywhere, and a population that sees walking through scenic agricultural land as a valid kind of recreation.

These last images are from Mürren, a recreational area with national-park-level scenery high the Bernese Alps, still part of the proud Canton of Bern. But this kind of infrastructure is everywhere in Switzerland. And of course there are also trains and buses, even in rural areas.

I’m a little reluctant to praise Switzerland for such abundant rural service, fashionable as that is, because it’s something you can do only if you have enough money. Most countries have to economise more, and so they face the fact that however much they would like to provide access to rural areas, the demand there is usually so sparse that it is not something you do if you want to attract many riders.

But Switzerland does have the money to spend on this. They can even afford to run frequent urban trolleybuses to cornfields. And who am I to judge?

Readers are pointing out that some of my old posts now have broken links to images. This is because Typepad, the blogging platform where my personal blog lived for 21 years, shut down on October 1. In early days of this blog, I sometimes linked to photos that I stored over there. Now those links are lost, and I don’t always have the images they referred to.

Readers are pointing out that some of my old posts now have broken links to images. This is because Typepad, the blogging platform where my personal blog lived for 21 years, shut down on October 1. In early days of this blog, I sometimes linked to photos that I stored over there. Now those links are lost, and I don’t always have the images they referred to.