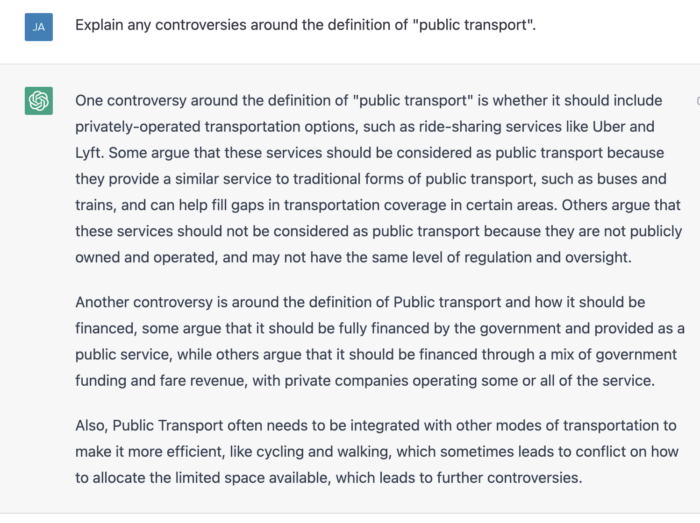

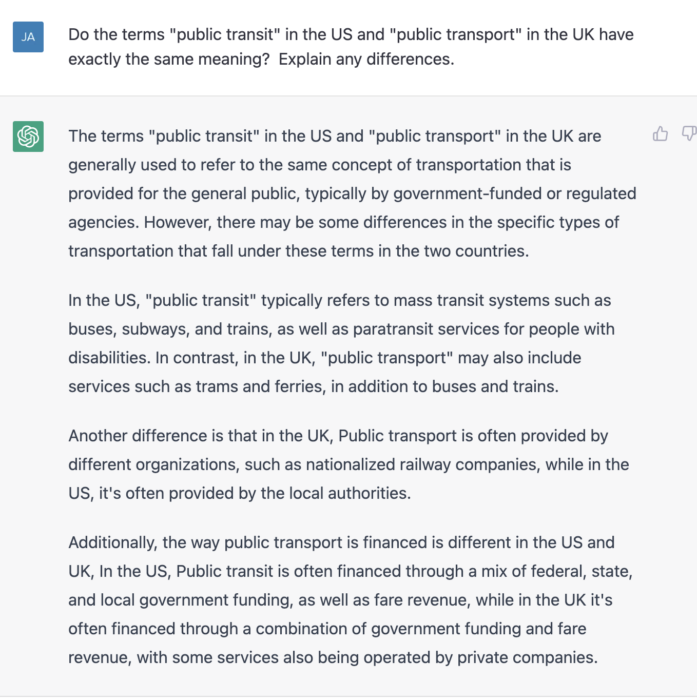

I frequently travel in places and situations where public transit isn’t useful, especially in the transit-poor United States. So I’ve been a frequent user of Lyft, a shared-ride competitor of Uber. It was an easy choice. Although the Lyft and Uber products are the same — often provided by the same cars and drivers — Lyft’s founders were credibly supportive of public transit, so their basic branding, “Uber with a conscience” or “Uber but nice” was pretty much directed at customers like me, although I had no illusions about where the ultimate profit motive would lead them.

I frequently travel in places and situations where public transit isn’t useful, especially in the transit-poor United States. So I’ve been a frequent user of Lyft, a shared-ride competitor of Uber. It was an easy choice. Although the Lyft and Uber products are the same — often provided by the same cars and drivers — Lyft’s founders were credibly supportive of public transit, so their basic branding, “Uber with a conscience” or “Uber but nice” was pretty much directed at customers like me, although I had no illusions about where the ultimate profit motive would lead them.

One virtuous thing that Lyft attempted was shared rides. For a lower fare, you could get a ride that would also pick up someone else along the way. This would reduce VMT and provide lower fares for fare sensitive folks, though still much higher than public transit fares.

I used this service once. On a departure from the airport, it paired my trip with one in a substantially different direction. The other trip was to a point further from the airport than my destination, and yet it served that trip first. I ended up with a travel time about twice what my direct travel time would have been, and much more than the app had estimated. I never used this option again. My impression was that they were overselling the product in contexts where it wasn’t appropriate, and they were offering the same discount to the person dropped off first — whose trip is exactly what it would have been if traveling alone — as to the person whose trip was being made much longer.

Drivers apparently hated it too, judging from many of the comments on this Reddit thread. They didn’t pay drivers enough to deal with the hassles, including customers not understanding the rules and poor relations between strangers sharing the car. Now, Lyft has abandoned shared rides, although Uber appears to be planning to expand them.

But shared-ride products are still needed, especially when demand appears all at once in high volume. A common scenario: A plane lands at a small-city airport at midnight. A line of 100 people ends up at the taxi stand. Taxis are programmed to carry single parties. In this situation I will usually poll the people around me in line to see if anyone shares my destination, which may be likely if it’s a downtown hotel. But we must then present ourselves to the taxi driver as a single party, or they will charge us more. It’s remarkable that in this particular case, late night airport to downtown, there isn’t a workable solution. Because while it can be a pain to have another person in the car, it would be even better to get to the hotel at 1 am instead of 3 am, and a small town with 17 taxis and a few Lyft cars is not going to serve us all very quickly if it insists on serving us all separately.

Of course, there should really be a bus to downtown meeting this late-night airplane, but planes are late a lot, and transit agencies can’t devote a bus to meeting an unpredictable arrival time.

If you are not a traveling businessperson like me, this may all sound very “first world problems” to you, but there is a lot of VMT in carrying a bunch of people from an airport to the same distant cluster of hotels at the same time, all in separate cars. I’m disappointed Lyft couldn’t focus this product on that problem, grouping people only when their destinations were very close together, and thus creating a product that both customers and drivers could be believe in.