The Apartment List Rentonomics blog, which writes on real-estate statistics and economics, recently posted a census analysis on the “Rise of Supercommuters”. It describes a recent increase in the percentage of people with commutes 90 minutes or longer each way. This thoughtful analysis is well worth a read. It finds that:

- Nationwide, one in 36 commuters are super commuters, traveling 90+ minutes to work each day, spending hours on public transportation or battling traffic.

- Super commuting is becoming increasingly common: the share of super commuters increased 15.9 percent from 2.4 percent in 2005 to 2.8 percent in 2016.

- The share of super commuters is highest in expensive metros with strong economies — New York, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Atlanta and Los Angeles, and in their surrounding areas.

- Super commuters are more likely to rely on public transportation than those with shorter commutes. An estimated 91.4 percent of non-super commuters drive to work, compared to just 69.7 percent of super commuters.

- In most U.S. metros, low-income commuters are more reliant on public transportation than high-income commuters, creating a nexus between super-commuting and poverty. When transit usage falls sharply with income it suggests that transit is used out of financial necessity rather than as a lifestyle choice.

But the term “Super Commuter” sounds too heroic. “Super commutes” aren’t something to celebrate. People should be free to arrange their lives this way, but shouldn’t be forced to by the housing market.

For the commuter, spending three hours of unpaid time a day commuting is only a response to a lack of reasonable alternatives. For taxpayers, it represents a high cost- both in providing infrastructure, and in increased traffic congestion. The US Census itself calls commutes over 90 minutes “Extreme commutes”. That to me, better describes these long commutes- they are something that a few people may have to do because of their job or family situation, but something that shouldn’t be made the new normal. “Extreme” also captures the right connotation. As in “extreme sports,” it suggests something that most people would rather watch than do, and that many don’t even want to hear about.

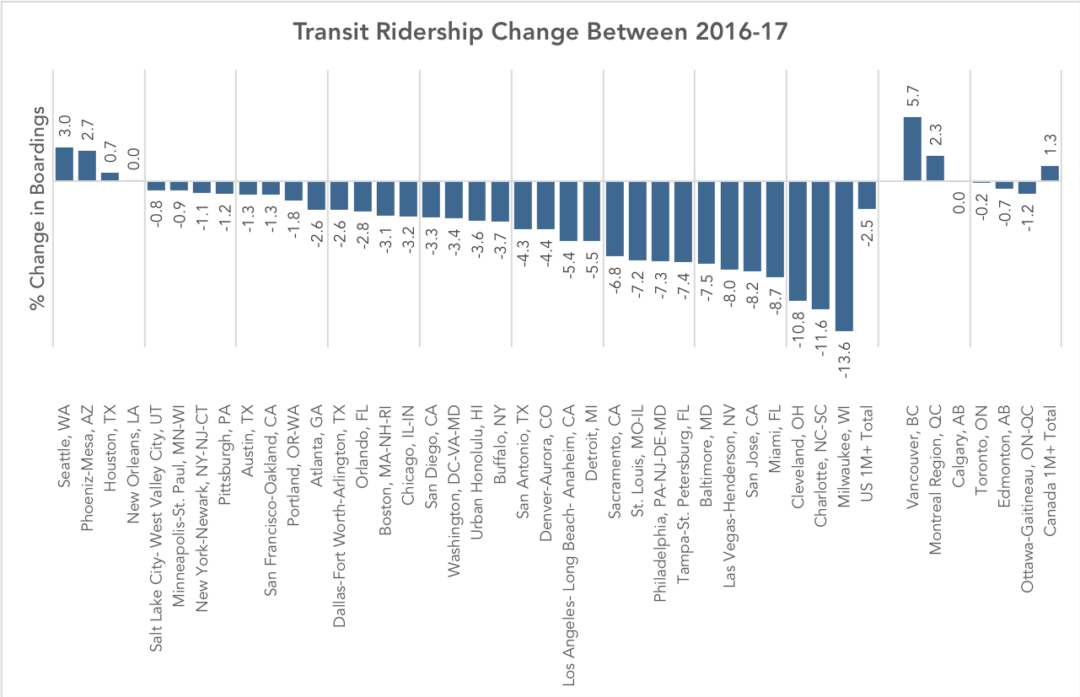

We can also draw parallels between increases in in the prevalence of these extreme commutes and the decrease in overall transit ridership over the past few years. They are both symptoms of the suburbanization of poverty, and to some extent, the middle class. These suburbs are not geometrically conducive to high-ridership transit, and as a result the transit options are poor, so many people who move there, resort to driving. But driving such long distances every day can cost thousands of dollars over the course of a year, so some people would still rather endure the low frequencies and limited spans of suburban transit service to access the city.

The article goes on to conclude that:

Reversing the growth in super commuting requires investment in both increasing housing supply and improving transportation.

Both increasing housing supply and improving transportation have the potential to reduce commute distances, but the location of this new housing and improved transportation are crucial. Transit always achieves higher ridership per hour of service in dense, mixed-use urban centers, than in unwalkable outlying suburbs, so if we want to reduce the percentage of transit commutes that take more than 90 minutes each way, we will have to substantially increase densities in places where fast, frequent, and useful transit is most feasible. That means a mixture of housing and jobs, and building up, not out.