(This series of posts on ridership-increasing bus network redesigns starts here, and its wrap-up is here.)

During the pandemic, we did a network redesign for Akron’s transit agency METRO. The agency covers all of Summit County, Ohio, the next county south of the Cleveland area. We already knew the neighborhood, having worked on Greater Cleveland RTA’s redesign a few years earlier. Evan Landman was our project manager.

Historically an industrial town, Akron has experienced the familiar rust-belt decline. There is still manufacturing, but it relies on a smaller and more diverse economy, including a university downtown, medical centers, and so on.

The agency had already adopted a Strategic Plan that called for a focus on the busiest corridors, while maintaining connectivity for people with the greatest level of need.

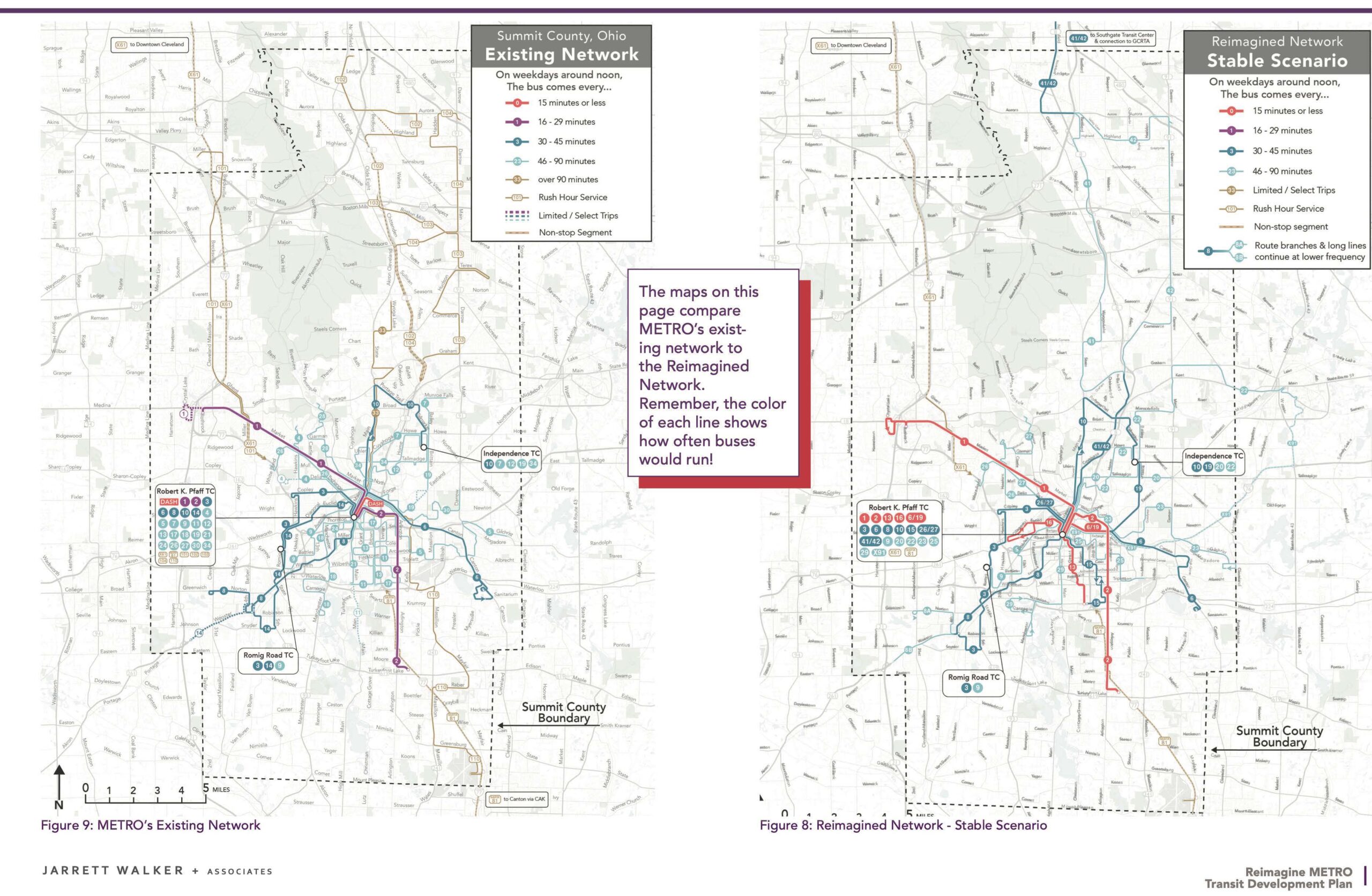

Here is the old network on the left, and the new network that emerged from the project on the right (click on all images to enlarge and sharpen.) Note the legend! As always on our maps, colors mean frequency, and that’s critical.

The old Akron network on the left, the new one (“Stable Scenario” on the right. Click to enlarge and sharpen.

A few things are especially worth noting here:

- The old network’s most frequent routes were every 20 minutes, just below the 15 minute threshold where service starts to really become useful. Because most other routes were every 30 minutes, there was no way to coordinate timed connections downtown.

- The old network had a downtown circulator that was just too short, and that could be replaced by a portion of a longer, more frequent line.

- The south central part of the city, a relatively low-income and diverse area, had a complex tangle of four overlapping routes that all came only once an hour. We replaced these with fewer, more frequent services that overlap each other less, a common way to increase access.

- We’re especially proud of what was possible in the vast rural area north of Akron, which borders the Cleveland urban area just off the map to the north. This area had an ineffective tangle of “express” services that ran just a few trips a day, and that were highly specialized around certain employers even though there wasn’t much ridership. The place replaced them with a simple pattern of a half-hourly service all the way from Akron to Southgate (north off the map) which is a major hub for Cleveland RTA services. The half-hourly service splits into two hourly strands in the rural area, to cover more territory, but converges at both ends to provide 30 minute frequency where demand is higher, and to provide 30-minute frequency all the way from Akron to Southgate. Our analysis of outcomes at the time showed that the Reimagined network would be immensely more useful in connecting people in Akron and Summit County to the places they need to go. In 45 minutes or less:

- The average county resident would be able to reach 60% more jobs using transit.

- The average person of color would be able to reach 88% more jobs using transit.

- The average low-income person would be able to reach 103% more jobs (more than double!) using transit.

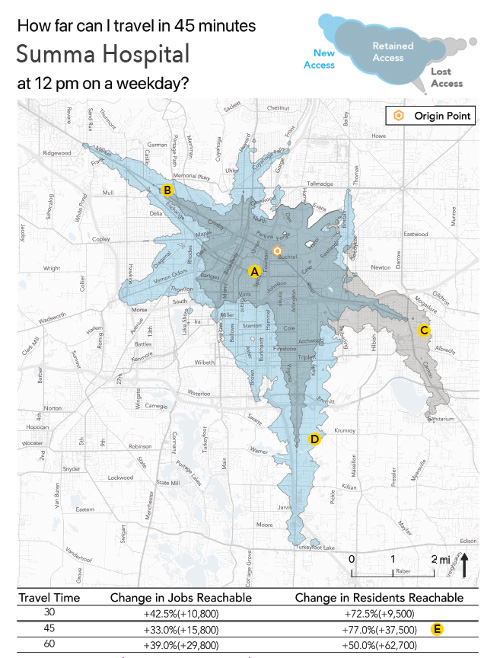

Major activity centers and destinations, such as Summa Hospital, saw even greater increases in access to people and jobs in the region. The isochrone example below shows how the new network increased the number of people who could reach the hospital in 45 minutes by 77%. These kinds of access gains are the reason we knew that this new network would improve ridership relative to the previous network.

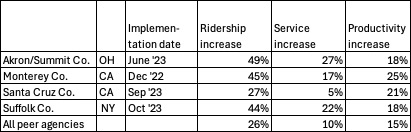

The Metro Board approved the Transit Development Plan in March 2022 and Akron METRO implemented the new network in June 2023. Ridership increased 24% in the first year after the network launched. As of July 2025, ridership was up around 40% compared to the year before the new network. (In our introductory post we cite a different figure because those figures are standardized to the period December 2022 to July 2025, for comparison to other redesigns.)

The Reimagined network was a significant expansion, adding about 27% more service, but it was also a huge step in the direction of being useful to more people. It is much easier to achieve major gains with more service, yet the access outcomes improved far more than the additional investment would suggest, indicating that the new network didn’t just expand service, it drastically improved ridership potential.

On net, the total network productivity (ridership relative to service hours) is up about 9% compared to the year before the new network launched. This is an extraordinary improvement in the context of overall trends in the industry.

The enormous improvements in ridership contributed to Akron METRO winning the 2025 APTA Outstanding Public Transportation System award for systems in the 3 million to 15 million annual riders category and the immense success was recently featured on the CBS Evening News: https://youtu.be/DNZnZJPvytU

We really enjoyed working with CEO Dawn Distler and the whole team at METRO. This is a remarkable story about how much network redesign can improve people’s lives.