Our whole urban form is heavily shaped by computer models that predict how much traffic a development will generate. Want to build a small residential-over-retail building in a walkable area? A conventional model will show that you need lots of parking, but also that you’ll generate lots of traffic on the nearby streets, which will provoke the neighbors to rise up to oppose the project. Since the model doesn’t think anyone will walk to it anyway, you might as well just build it out by the highway.

Hence, our suburban landscape.

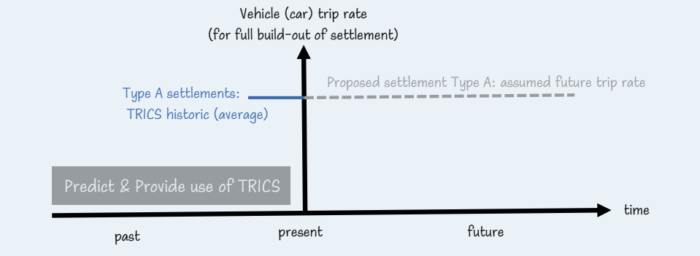

It all goes back to the transport planning ideology called “Predict and Provide.” When predicting how much vehicle traffic a development will generate (its vehicle trip generation rate) the model looks at what similar developments have generated in the past, and just assumes that will continue.

Predict and Provide model: The future is just like the past. Nothing you can do about it. Source: TRICS Guidance Note, February 2021

If the community isn’t changing, and the world isn’t changing, this might work. But of course, the very fact that you’re proposing a development means that the community is changing. It’s growing, which means car-dependence is on its way to hitting known limits where congestion starts to affect behavior. Meanwhile, the world is changing: people want to live in more walkable communities, and there are many incentives to encourage them. The classic “Predict and Provide” model tells us to ignore all that. It presumes that you are a copy of your parents and that when you’re their age, you’ll behave exactly they way they do.

Some of us have been pointing this out for years. The transport modeling industry sees the problem and has been softening its predictive claims, but the fact remains that the biggest investments, large infrastructure and real estate development, require everyone involved to (pretend to) believe predictions. Even if everybody in a process knows now ridiculous the assumptions are, the easiest thing to do (and often the legally mandated thing to do) is to perform the process.

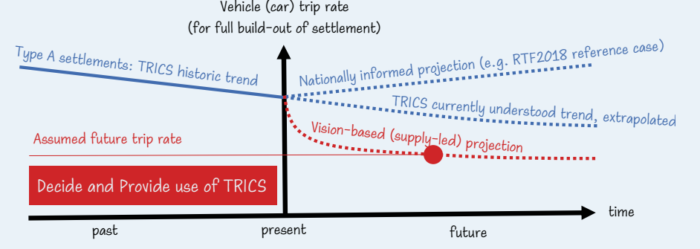

So it’s great to see the emergence, in the UK, of the “Decide to Provide” paradigm. It is now being recommended by the very people who curate the UK’s dominant transport model, TRICS. It says that when describing rates at which a development generates traffic, it’s appropriate to have a “vision” scenario showing the most credible optimistic outcome.

Decide and Provide. There are several credible futures. Which one do you want? Source: TRICS Guidance Note, February 2021

You can”t predict the future, but you can predict a range of credible possibilities, and then think about which one you actually want.

Maybe the trip generation rate will rebound (the “Nationally informed projection”). Maybe it will continue its slow descent. Or maybe what it does will depend on your vision for your whole community, and your resolve in implementing that vision. If you want a more walkable community, this model holds open the possibility that you might succeed.

The “vision-based” curve is “supply-led” because it’s based on the widely observed principle (and biological axiom) called induced demand: If you make something easier, people will do it more, and if you make something harder, they will do it less.

The “supply-led” curve is what happens if you limit road space and parking, while making it easier to walk, cycle, or take public transport. Obviously this has to be done in the right place, where there is already a critical mass of walkable development, or where there’s a viable plan to create such an area at sufficient scale.

Should you seek to shift demand away from driving? It’s a choice, arising from a set of values. But “Predict and Provide” was also a choice, expressing a set of values. There never was neutral or factual way to predict trip generation. There was only a culturally dominant one.

Every time we undermine the illusion of predictability, we expand our freedom to choose!