At the moment, everyone is playing with ChatGPT, the new open-access Artificial Intelligence (AI) tool that is able to write remarkably clear prose in a range of styles. You can play with it here.

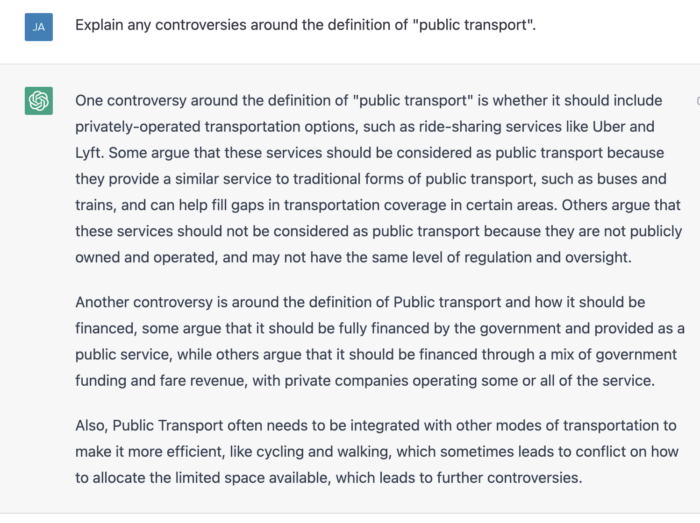

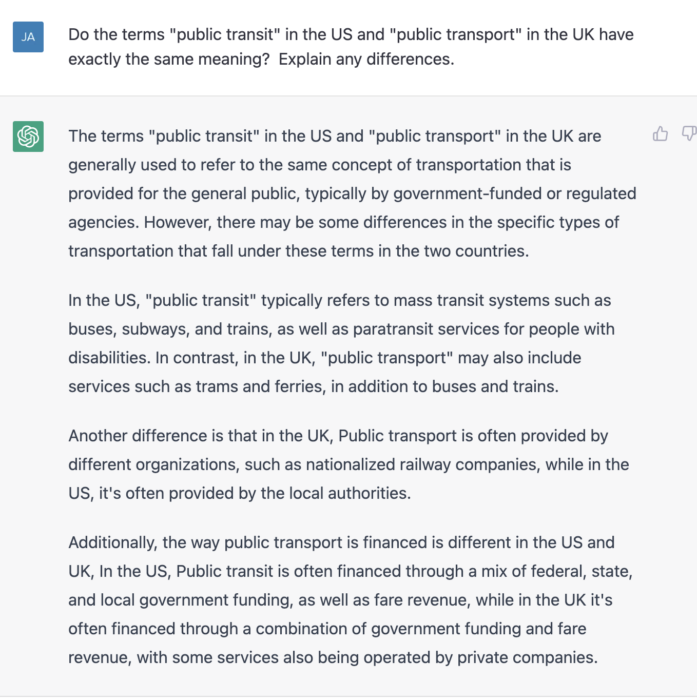

I knew it had passed all the easy tests, so I tried to throw it into the deep end:

So I think: OK, this isn’t intelligence. This thing isn’t thinking about the topic. It’s just collecting relevant scraps of chatter from the world, sorting the chatter into boxes, and giving me a tour of the boxes. Doing that requires some pattern-recognition skills, but it’s not thinking in the fullest sense of the word.

Only the first of the three paragraphs is an answer to my question. After that the program is just riffing. If this were a high school paper it would get a middling grade for lack of focus on the topic.

But the first paragraph is on-topic, and it’s evidence of how thoroughly Uber and Lyft have succeeded in owning large parts of the bandwidth of public chatter. Roving the internet, and lacking any other reference points in reality, ChatGPT has decided that since the “Uber is public transit” meme has been so effectively amplified, that must be the most interesting definitional issue.

So let me see if I can be smarter than the computer. This, which I just wrote, is an example of actual thinking:

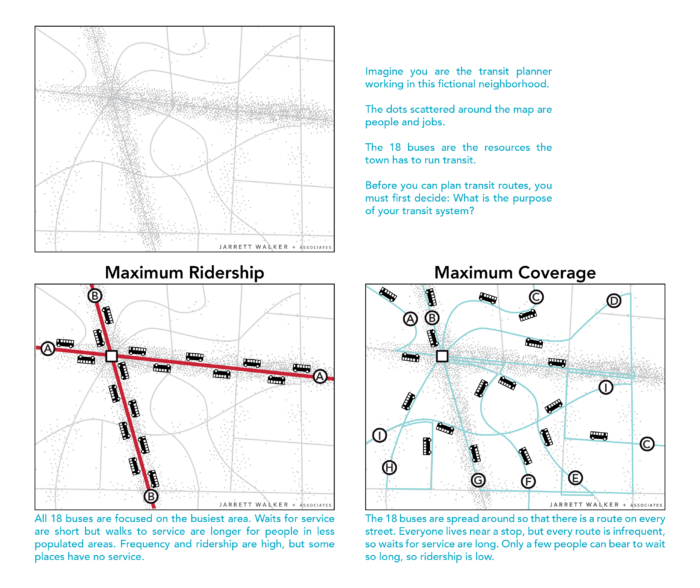

The term “public transit” (“public transport” outside North America) has long been used to denote passenger transport services that allow many people to ride in the same vehicle even though they are not intentionally traveling together, or even going to the same places. The term is usually limited to services traveling within an urban area or for similar short distances; long-distance intercity services are not included in the typical usage. Finally, these services are open to all paying passengers, and are thus “public,” regardless of what mixture of public and private sector is involved in providing them.

This definition is an attempt to describe actual usage. In other words, when people say “public transit” they almost always mean things that meet this definition and not things that don’t.

However, where public transit is a popular idea, there is an understandable impulse to extend its definition to adjacent concepts that a speaker wants to promote. So you will sometimes hear that taxis, Uber and Lyft should be called public transit, even though they are designed to transport only one travelling party at a time.

It is easy to say that this extension of the definition is just wrong, because strangers sharing a ride is a common feature of all public transit as the term is traditionally used, and that’s not what these services are.

But of course, definitions are never right or wrong. They are not facts but conventions. A sufficient consensus around any definition will make that the truth, because words have meaning only through how they are used.

A better argument against extending the meaning of public transit to include taxis, Uber, and Lyft is that the resulting term would no longer correspond to public transit’s reputation as a solution for important problems. Many of the most important benefits of public transit, especially around emissions and the efficient use of urban space, arise only from public transit carrying many people in the same vehicle.

From this point of view, extending the definition to cover taxi-like services can fairly be described as dishonest. Promoters of these services want them to be called public transit because public transit is seen as a good thing, but if these services don’t actually provide the outcomes that most people associate with public transit investments, then those people have been misled.

This is thinking. It goes beyond the journalistic formula of “some people say this and some people say that.” Instead, it looks into the actual issues at stake, and considers what definitions are for. It is also narrowly focused on the task of definition, as distinct from just throwing out a lot of chatter about adjacent questions, as ChatGPT and mediocre student papers will do. Finally and most important, it risks being wrong.

To verify this, I asked it an even more focused question:

ChatGPT correctly states that the two terms are largely equivalent. Then there’s a paragraph of nonsense trying to make distinctions based on modes. It thinks trams are part of the UK definition but not the US one, but that’s only because the word is different (tram in UK, streetcar in US). It has never heard of a ferry being called public transit in the US, so it clearly needs to spend more time in San Francisco. In short, the chatter in the world about public transit is heavily about modes, so ChatGPT assumes that must matter somehow to the question of definition. As with the taxi question, it is mistaking amplification for meaning.

Then the last two paragraphs are completely off topic — just as the last two paragraphs of the previous answer were. They’re about public transit, but I didn’t ask for a summary of all the differences between the US and the UK. I asked about the meanings of the two terms, “public transit” and “public transport.”

So again, this thing writes great mediocre student papers, and its prose style is good, but it’s not ready to use philosophical concepts, such as definition, in its own thinking.

To check this conjecture, I asked:

For now, I guess that’s my answer.