Everyone gets frustrated with transit agencies. The people inside of them get frustrated too.

But spewing rage at a transit agency rarely has much effect. Making good arguments does better but you will still find resistance. Elected officials have an impact, but if their direction is confusing or contradictory, it may not be the impact they intend.

As often, if you really want to influence someone, you have to start by thinking about things from their point of view.

I’ve worked with over 50 transit authorities, of various sizes, in many countries. I’ll talk here mainly about the US transit agency, but much of what I’ll say is relevant in other countries. My goal here is not to defend anything a transit agency does, but just to suggest ways to be more understanding of the agency’s experience, which will make you better able to influence them.

Regulations

If you run a business, you may be frustrated with all the laws and regulations that limit your ability to do the right thing fast. But this is nothing compared to what transit agencies deal with every day.

In the US, transit agencies don’t just obey the laws that every employer or transport company obeys. Much of their money comes through the Federal government, and receiving this funding requires satisfying all kinds of Federal requirements. These regulations go beyond laudable goals like safety and civil rights. They specify detailed procedures that must be followed in many kinds of activity. Everything, from labor relations to service planning t0 the design of major planning studies, happens in the context of this web of Federal requirements, and like all webs (in the spider sense) these limit your range of movement and slow you down.

I’m not commenting on the worth of each of these regulations, but can certainly testify to their cumulative impact. I’ve seen countless situations where elected officials were demanding that something get done fast, and the correct answer was that Federal mandates and processes simply prohibit that.

Rigid Labor Structures

Until the uptake of automation, transit will be a labor-intensive industry. Labor is around 2/3 of a typical transit agency’s operating costs. The cost to run a bus for an hour obviously governs how many bus-hours of service you can run, and this cost, which is between $100 and $200 in most US urban agencies, turns centrally on the deal between the transit agency and its labor unions.

What matters is not just the pay rate and benefits (which are complicated enough) but also the rules of work. These can be very intricate, and their impacts can cost a lot of money. Once the contract is set, the rules, no matter how bizarre or costly their impacts, define what’s possible.

Labor-management relations are legally structured to be adversarial, and adversarial relationships are always inefficient. That’s not the fault of anyone working in the system now, on either side.

There is no neutral definition of what’s fair. Both sides push for whatever they can get. Most big cities have progressive elected officials who care about both transit workers and transit riders, but both of those voices have to be strongly present in the conversation, because ultimately they want opposite things. You’re not going to get more bus service if the cost of an hour of service is going through the roof, so you have to want labor compensation and work rules that are fair but not outrageous.

(By the way, I’m a strong supporter of unions, but please don’t be distracted when they talk about what the senior managers are paid. Those are trivial numbers compared to a transit agency’s labor-driven operating budget. If you want great transit, don’t demand that managers be paid less. Demand that they hire excellent managers.)

Confusing Direction from Elected Officials

When elected officials first find themselves in charge of transit, they may not know much about the topic, and can have trouble figuring out what to do. It’s like that famous nightmare where you find yourself seated at a piano onstage, with a huge audience looking at you, but you never learned to play the piano.

So elected leaders need some training on the facts and choices that they’ll face. If you’re going to drive a transit agency, you have to know where the controls are, what happens if you push this button, and how to avoid hurting yourself or others. Not all transit managers think it’s their role to educate their elected boards, because this can feel like criticizing your boss.

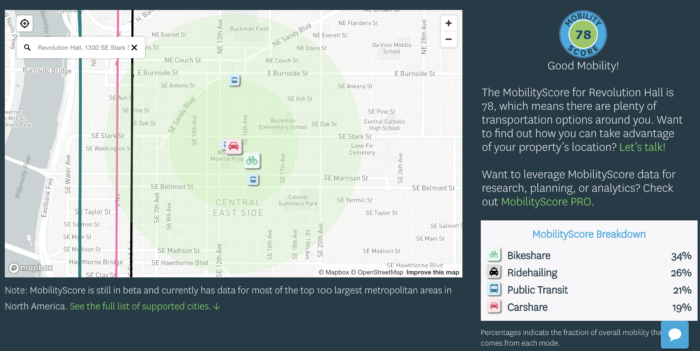

So without intending to, elected officials often give direction that causes confusion or anxiety in the transit agency. A great example is the conflict between ridership and coverage goals, which I explain here. If you demand both ridership and coverage from your transit agency — and most people do want both — then you’re giving contradictory direction, and someone needs to force you to be clearer about what the priorities are. This is a role my firm often plays in transit studies.

Finally, there’s no consensus on what core body of knowledge a “transit expert” should have; this is the starting point of my book Human Transit, and discussed more detail in its introduction.

Operations as Resistance to Change

The dominant task of most US transit agencies is running the service every day, and most staff are focused on that. In operations, your goal is to make the service the same today as it was yesterday. Disruption is your enemy.

S0 when some egghead planner shows up wanting to change the transit system, it’s easy to see them as just another disruption — not fundamentally different from the car crash blocking the your rail line. I’ve been that egghead for many transit agencies, so I’m used to the particular kinds of resistance that often (not always) come from the operations side. I don’t criticize them for reacting this way. They’re doing what they were trained to do, which is keep things steady and predictable, as we all want transit to be.

Because operations is the dominant part of most agencies, it’s easy for this aversion to change to define the whole agency’s culture. It takes great management to keep operations staff feeling valued and supported even as you contemplate major changes — even “disruptions” — to how you do business.

Misdirected Blame

Many aspects of the the success or failure of a transit system is outside the transit agency’s control.

When a bus is late, do you blame the city that decided not to have bus lanes or other transit priority, or do you just blame the transit agency?

When a planning process seems bureaucratic and unresponsive, do you blame the Federal rules that they have to follow, or do you just blame the transit agency?

When it’s hard to walk from a bus stop to your workplace, do you blame the road department that designs and manages the street, or do you just blame the transit agency?

When you see a transit agency’s ridership falling, do you consider outside causes like low gas prices? Do you consider non-ridership goals the agency may be pursuing? Or do you just assume that the agency is failing?

If there isn’t enough service in your area, do you blame the elected leaders (and voters) who refuse to fund transit properly, or do you blame the transit agency for serving someone else when they should be serving you?

Transit agencies are constantly blamed for things they don’t control, which leads to …

Public Abuse

Screaming abuse at your transit agency staff is not a good way to get them to do things. But it does have an impact: It makes the transit agency more defensive, and less likely to be open with ideas and information. The best transit managers are also hard to keep in this situation, because there are probably other jobs they could do that don’t require taking so much abuse.

There’s a deep sadness at the heart of transit operations, which is that when you do it well nobody thanks you. Your job is to be invisible. When you become visible, it’s when people scream at you because you’ve done something wrong. If that’s your daily experience, of course you’ll keep your head down, not speak up, not share ideas. Or as a seasoned Australian transport bureaucrat told me years ago: “The key to success here is to say as little as possible.”

I’m just thinking of the management staff’s role taking abuse, but that’s nothing compared to the bus driver’s. People yell at them and argue with them all day. Those who maintain good cheer (and safe driving) under all that pressure are absolute heroes in my book.

Finally, some journalists write in ways that amplify the abuse. I’ve worked with some excellent transit reporters, but also I’ve faced some who are sure I’m deceiving them just because I’m sharing information that doesn’t match their prejudices. I’ve also used to mainstream media stories that misuse data to make stories of transit failure sound more extreme than they are. They deserve pushback from people who care.

When people are abusive toward you, does that make you want be more open and vulnerable, as you need to be to really engage with others? Me neither. No wonder transit agency staffs seem a little defensive sometimes.

I wrote more about the paradoxes of public communications here.

To Sum Up

It’s totally OK to be unhappy with the quality of your transit system. The best people on your transit agency’s staff almost certainly share your opinion. By all means press your transit agency to improve, but take the time to understand what the real barriers are, which will help you see where advocacy is really needed.

If you want to influence a person, you start by listening to them, understanding what it’s like to be them. Try treating your transit agency the same way.

Scudder was our client, in effect, for two years before joining us, as we collaborated on the

Scudder was our client, in effect, for two years before joining us, as we collaborated on the