This is going to sound a little like marketing, but it answers a common question or objection.

This is going to sound a little like marketing, but it answers a common question or objection.

Why do you need consultants for your city’s transit plan? Other consultants will speak for themselves, but here’s why you might need a consultant like me. Inevitably, this list is also a definition, in my mind, of what makes a good consultant, at least for transit network design. It’s what we strive for at our firm.

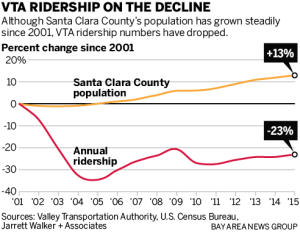

- Experience with Lots of Cities. Your city is unique, but the facts of geometry, the facts of biology, and many human longings and foibles are the same everywhere. I’ve worked in (or studied) about 100 cities and towns, so I can see what’s unique about your city and exactly what’s just like everywhere else. This perspective is helpful to locals, who don’t all get to make that comparison every day. In particular, I can help you take some of the fervor out of local arguments by pointing out that many cities, at this moment of history, are having the very same conversation, featuring the same points of view.

- Ability to Foster Clear Conversations. Because of that experience, we cut through a lot of angry chaos in the local conversation, and frame questions more constructively. This doesn’t mean we make hard decisions go away; in fact we often make them starker. But we also make them clearer, so that if the community makes a decision, they actually understand the consequences of that decision.

- Maximizing Your Community’s Options. Unlike a lot of consultants, we hate telling communities what they should do. We prefer to show them what their options are, and let them decide. But laying out options is really hard. You have to show exactly where the room to maneuver is where where it isn’t. That requires the next two skills.

- Clarity about Different Kinds of Certainty. As consultants, we know when we’re in the presence of a geometric fact rather than a cultural assumption or a personal desire. Only when we accept the facts of geometry (and biology, and physics) can we know what a community’s real options are.

- Ability to Argue from Shared Values. Good transit consultants don’t just talk about peak loads and deadheading and value capture and connection penalties. They also talk about liberty and equality and durability and prosperity and aesthetics. Then, they explain why those big ideas for your city imply that you should care about this or that detail of your transit system.

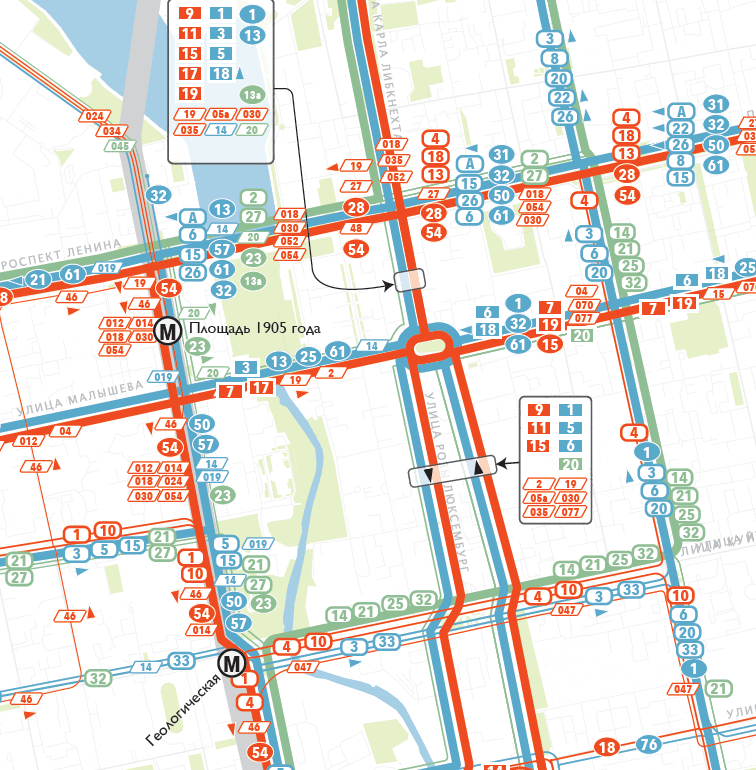

- Skill at Synthetic Thinking. Synthetic thinking is the ability to generate insights that solve many problems at once. It’s what you need to do to create a scientific theory or design any complex system. Synthesis means “putting things together,” so it’s the exact opposite of analysis, which means taking things apart. Synthesists rely on the work of analysts, but you will never analyze your way to a good network design. The skill of synthetic thinking is impossible to teach and can only be recognized where it appears, but a fondness for thinking abstractly or theoretically is a good indicator of it. And since network design is rarely taught in universities anyway, the best evidence of this skill is a track record of having done it successfully, in lots of cities, plus (very important) the ability to explain it to a diverse range of people.

- Skill at Spatial Thinking. Finally, the specific kind of synthetic thinking needed for network design is spatial. People who like designing and solving problems in space — architects, military strategists, chess players, visual artists, and kids or adults playing with trains — are likely to be good at it.

The biggest public transit authorities, in the most transit-sophisticated cities, may have people with all these skills on their staff, because they are questioning and improving their network all the time. But most transit agencies don’t, and that’s understandable. In most cities, you don’t redesign your transit network every day, or even every decade, so it’s inevitable that most of the staff of the transit agency has never done it before. Relatively few transit agency jobs require, on a day-to-day basis, the skills that make for good network designer, especially for large-scale redesign. So those agencies will benefit from some help.

Consultant, of course, is a much-sullied word. For one thing, many consultants go around telling people what they should do; we do this as little as possible. Many consultants just teach you to envy other cities, which appeals to certain human desires but is also not the best basis for good decisions. Some consultants speak in ways that are incomprehensible to most people, or refuse to explain things clearly, so as to sound wise or authoritative. (“Our proprietary six-step model with a Finkelstein regression says you should build this freeway.”) A consultant who can’t make a reasonably intelligent and open-minded person understand their work isn’t one you should trust — especially when it comes to network design.

See, network design is like chess. The rules are pretty simple. I explained them in my book Human Transit and in this blog’s Basics posts, and I keep trying to improve on those explanations, here for example. But doing it is hard, and you can spend years getting better at it. So it helps to have someone at the table who has done it many times, who knows how to see the patterns of opportunity in your city’s geography, and who can explain why an idea works, or doesn’t.

When Jane Jacobs died 10 years ago, I wrote this

When Jane Jacobs died 10 years ago, I wrote this