… or as the City of Edmonton calls it, the frequency-coverage tradeoff, which is fair too. We’re proud of our role in getting this conversation started, with City Council workshops a couple of years ago …

Author Archive | Jarrett

Job in the Sun: Senior Planner / Scheduler for Palm Beach County Transit

Just got home from a great trip to Palm Beach County, Florida, where I sampled the famous walkability of West Palm Beach (and Palm Beach) and had a series of workshops and public events with PalmTran, the local transit agency.

PalmTran is at that point where it needs strong planning leadership. They will have Senior Planner / Scheduler position open in May. This job needs someone with a track record of finding efficiency in schedules and routes, managing difficult data sources, thinking geometrically about network structure, and leading a planning team. $90,ooo/year.

Palm Beach County is the geographically largest county in the eastern US, with an interesting mix of vibrant coastal cities, barrier island cities, typical postwar suburbia, and rural Everglades communities. Many of its key cities are serious about walkable urbanism — West Palm Beach is the most famous, but many others are making the effort.

If you’re interested, please watch the website at palmtran.org and email an application to [email protected]

The Best of April 1 Transit News (ongoing)

Self Driving Cars Likely to Restore 70% of Lost Faith in Humanity. (Planetizen)

Google Netherlands (who else?) Invents the Driverless Bicycle (Excellent YouTube Video of Dutch people being adorable as usual.)

With typical tech-bro grandiosity, inventors promise that Duck Rapid transit will abolish that old fashioned subway system in Washington DC. (Greater Greater Washington).

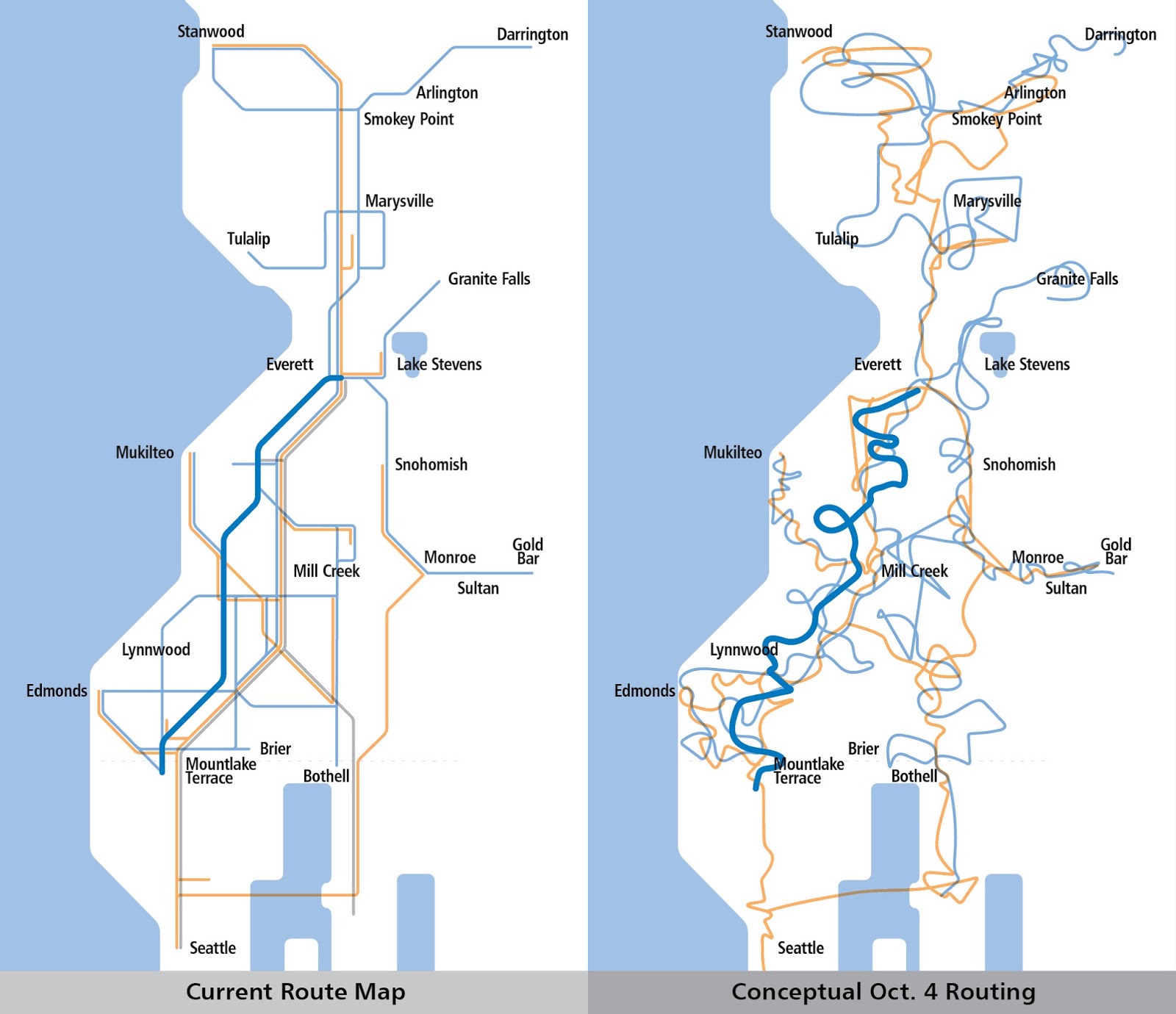

Community Transit (Everett, WA) will celebrate 40th Annversary by running its 1976 network on October 4. Helpful diagram:

I’ll add more as the day progresses. Send links to your favorites.

Some Common Transit Analysis Mistakes

There’s more data than ever, so there are more ways than ever to draw brightly colored maps of supposed transit facts. But that means it’s also easier than ever to take common types of confusion about transit and make them look like the outcomes of analysis. Your results will always reflect your assumptions, and a lot of transit analysis is still built on common mistakes that are completely obvious if you stop to think about them.

Case in point today, US Department of Transportation wants to undertake a National Transit Map project. This seems to mean drawing all the nation’s transit data feeds into a national database, which is certainly a good thing. But everything depends on the assumptions being made, and the initial video — recommended on Twitter by its narrator, Dan Morgan of USDOT — is not encouraging. The big mistakes can all be found in a 3-minute stretch starting at 5:00. Here’s the video.

The three big mistakes are:

- Implicitly confusing land area with population in visual representations. Starting at 5:00, the video presents a map of intercity access by car and train. The “discovery” from this analysis is that Amtrak doesn’t stop for several hundred miles as it crosses West Texas. It looks like a gap on the map, but it’s not a gap in reality because there are almost no people there. Of course, people draw maps like this all the time (we’ll see a lot of them during election season) but good analysis provides some visual cue to caution the viewer that land area, which is what jumps out on maps, has nothing to do with people. For example, this map could have been superimposed on a map of population density.

- Assuming that having transit nearby is more important than transit being useful or liberating. At 6:00 we see a map of the part of Salt Lake City in walking distance to transit, showing obvious gaps.

This makes the previous mistake (there’s no indication of whether anyone lives or works in those gaps) but more importantly, it gives the impression that the primary problem with transit is that it doesn’t cover more area. In actual transit systems with fixed budgets, the area you cover will be inversely related to the frequency, speed, and reliability you can offer, which means that a transit agency that spreads itself thin tends to offer services that are useless to almost everyone. This geometric fact is the basis of the ridership-coverage tradeoff problem. When we see analyses that imply that transit’s problem is that it doesn’t go enough places, we need to recognize this as implying an advocacy of coverage over ridership, and more generally an advocacy of spreading service so thin that none of it is useful to most people’s lives.

This makes the previous mistake (there’s no indication of whether anyone lives or works in those gaps) but more importantly, it gives the impression that the primary problem with transit is that it doesn’t cover more area. In actual transit systems with fixed budgets, the area you cover will be inversely related to the frequency, speed, and reliability you can offer, which means that a transit agency that spreads itself thin tends to offer services that are useless to almost everyone. This geometric fact is the basis of the ridership-coverage tradeoff problem. When we see analyses that imply that transit’s problem is that it doesn’t go enough places, we need to recognize this as implying an advocacy of coverage over ridership, and more generally an advocacy of spreading service so thin that none of it is useful to most people’s lives. - Focusing on peak hour service when discussing the access needs of poor people, even though most low-income people need to travel at all times of the day, evening and weekend. Starting at 6:55, we get an analysis that identifies poor people who do not have good access to rush hour transit. Poor people are rarely rush-hour commuters and they go many places other than the downtowns on which most peak service focuses.

I’m sure the analysts behind these examples thought that they were simplifying in a useful way. In my consulting work we simplify all the time. But we are careful to simplify in the direction of clarity about reality, rather than in the direction of helping people feel good about their often-false assumptions. The simplifications in this video — and of so much transit analysis still — are of the latter kind.

My New Article on Transit’s Space Efficiency

You may have seen my recent Washington Post piece on why fixed route transit will always be essential. Here’s my deeper dive for the Southern California Association of Governments Vision 2040 report. It focuses more specifically on how a focus on geometry can help us be smarter about prediction. Most important paragraph:

If you can recognize a problem as geometric — such as the need to use space efficiently in cities – you can become a smarter consumer of predictions. Cities will always have relatively little space per person, so no matter what technologies we invent, the amount of space that things take will always matter, and we’ll have to use that space wisely.

How International is Human Transit?

While I live in the US now, we’ve always had an international readership, and I’m happy to say that this is more true that ever, as you can see in the table below. In per-capita readership over the last year, the US ranks fifth, after four other countries that I’ve worked in extensively: Iceland, New Zealand, Canada, and Australia. (The last two are also countries I’ve lived in.)

New Zealand has led these rankings for years, but Iceland’s population is so small that it wasn’t hard for it to take first place once I started working there last year.

Among developing countries, Malaysia just grazes the top 20 and the highest-ranking is Trinidad and Tobago, though given the small population, that could have been one avid reader checking every post. Hey, if you read this blog in Trinidad and Tobago, say hi! I don’t know who you are yet!

Per Capita Readership of Human Transit Blog, year ending 28 March 2016

| Annual Sessions | Pop 1000s | Sessions/1k pop | |

| Iceland | 604 | 333 | 1.814 |

| New Zealand | 6799 | 4,675 | 1.454 |

| Canada | 46792 | 36,048 | 1.298 |

| Australia | 28422 | 24,039 | 1.182 |

| USA | 211769 | 323,137 | 0.655 |

| Singapore | 3559 | 5,535 | 0.643 |

| Finland | 2325 | 5,491 | 0.423 |

| Ireland | 1471 | 4,635 | 0.317 |

| UK | 19485 | 65,097 | 0.299 |

| Israel | 2506 | 8,476 | 0.296 |

| Sweden | 2759 | 9,858 | 0.280 |

| Hong Kong | 1951 | 7,324 | 0.266 |

| Trinidad/Tobago | 260 | 1,350 | 0.193 |

| Netherlands | 3035 | 17,001 | 0.179 |

| Switzerland | 1180 | 8,306 | 0.142 |

| Belgium | 1570 | 11,312 | 0.139 |

| France | 6084 | 64,529 | 0.094 |

| Germany | 6934 | 81,459 | 0.085 |

| Malaysia | 2378 | 30,901 | 0.077 |

| Spain | 2112 | 46,423 | 0.045 |

“This Is Our Reality”: Pushing Back on Abuse of Transit Staffs

Last week, Taylor Huckaby was manning the Twitter feed at San Francisco’s regional rapid transit agency, BART, during a tough morning. Mysterious electrical faults were causing cascading delays, and Twitter boiled over with rage. Suddenly, Huckaby started tweeting in ways that got attention.

Quite deservedly, this and 57 similar tweets went viral, even making it to the New York Times. Vox, one of the more transit savvy of US national media outlets, got it right: BART “stopped being polite and got real.”

Inspired by Huckaby, let me put this more generally: Politeness and deference are always the first impulse of transit staffs dealing with the public, but sometimes politeness turns into a habit of apologizing for everything and anything, and at that point, staff is consenting to abuse. Few public servants take as much public abuse as transit agency staffs do, almost always because of problems that are out of their control.

Imagine Huckaby’s position. His job is to communicate on BART’s behalf, but because of decades of decisions by past leaders (regional, state and national, not just at BART), his beloved transit system is betraying its customers. It’s certainly not Huckaby’s fault. In fact, he understands the issues well enough to know that it’s probably not the fault of anyone working at BART today.

In this situation, the usual vague apologies would amount to misleading the public. Huckaby deserves his heroic moment, because he did exactly what transit agencies need to do: Find the courage to say the truth, because while people will yell at you when you do, nothing will ever improve if you don’t. But don’t let me make that sound easy; it’s not.

Some of the early coverage, including that Vox piece, gave the impression that Huckaby had just snapped, “lost it,” gone rogue, but Huckaby has now spoken up to justify his comments, stand up for transit staffs, and properly blame some of BART’s problems on a broader US tradition of infrastructural neglect. BART management seems to have his back, and Los Angeles Metro tweeted this great video snippet, suggesting that they do too.

Mad at how bad your transit service is? Maybe the problem is with people and cultures at the agency now, but maybe it’s because of decisions made at higher levels — regional, state, and federal — often outside the agency. It’s easier if all those people if the frontline staff takes the blame, and are trained to just apologize all day. But that never solves the problem, and what’s more, it’s abuse.

South Florida: Speaking on March 24

On March 24 at 1:30 PM I’ll be doing a presentation to the board of the Palm Beach County transit agency, PalmTran. Conveniently, it’s in Boca Raton at the south end of the county, so it’s not too far from Fort Lauderdale or, for the truly motivated, from Miami.

This is part of a new network review initiative from the new Executive Director, Clinton B. Forbes. Obviously the presentation will touch on Palm Beach County examples, but much of it will be of general interest.

It’s unusual to have a board meeting noticed as a public event, but PalmTran is encouraging one and all to come. It’s from 1:30 to 3:00 PM at the Boca Raton Municipal Building, 6500 Congress Avenue in Boca Raton. The contact for further info is Steve Anderson, [email protected]. No RSVP appears to be required.

Some Reads on the Maintenance Crisis

The one-day shutdown of the Washington DC Metro is a useful call to arms about the dreadful state of maintenance in some of the US’s major rapid transit systems — a subset of a larger issue about deferred maintenance in all kinds of infrastructure. If it seems like this makes the US like the developing world, NPR reminds us that most developing world metro systems are in much better shape. (My Moscow correspondent Ilya Petoushkoff was also quick with an email reminding me that when even one Moscow subway lines go down, emergency bus lanes are created with Jersey barriers.)

The Washington Post’s Philip Kennicott is also fine on how the subway’s failure ties to great themes of US urban decay.

I have no opinion about the wisdom of DC Metro CEO Paul Wiedefeld’s decision to shut down the subway for a day to inspect faulty wires, except that it seemed sudden and left little time for preparation. Its attention-grabbing effect was unmistakable, and perhaps that was necessary to shock everyone into understanding the urgency of the problems. But it doesn’t appear to have been a PR stunt: the system’s faulty wiring had already caused a fatality, and sure enough, the one-day shutdown to inspect these wires turned up even more dangerous ones.

But do read this Vox piece by Libby Nelson on how transit agencies can be more honest with their customers, including on Twitter. Bravo to the Bay Area Rapid Transit for telling customers the truth about the problems facing the agency — which is to say, facing the region.

San Jose and Silicon Valley: Follow our VTA “Next Network” Project

One of our big projects this year is a Transit Ridership Improvement Program for the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, which serves San Jose and Silicon Valley in California. A key piece of that will be the “Next Network,” to be implemented in 2017 with the opening of the BART extension into San Jose. The Next Network is about more than accommodating BART. It’s also a chance for citizens to help the agency think about its network design priorities.

One of our big projects this year is a Transit Ridership Improvement Program for the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, which serves San Jose and Silicon Valley in California. A key piece of that will be the “Next Network,” to be implemented in 2017 with the opening of the BART extension into San Jose. The Next Network is about more than accommodating BART. It’s also a chance for citizens to help the agency think about its network design priorities.

I’m happy to announce that the project website is now live, and that our first report, called a Choices Report, can be downloaded here.

A Choices Report is our preferred term for what is often called, tediously, an “existing conditions” report. (Has anyone ever looked forward to reading about “existing conditions”?) The report does cover existing conditions — the performance of the transit service in relation to the markets it serves — but with an eye toward revealing insights that lead to a better understanding of the real choices an agency faces.

The Choices Report will form the background for a series of three network alternatives that will be shared with the public over the summer. The whole point of those alternatives is to encourage you to think about different paths VTA could take. A final network plan is expected near the end of this year, to be implemented when BART opens in July 2017.

The public conversation in this project is not a thing we do on the side. It’s the whole point of the study. We need robust public participation in this project to help sift the alternatives and make sure we’re heading in a direction that the community can support. So please, if you live in the region, bookmark the project page, and watch for updates there and here.