This page is available in English here.

Durante el último año hemos estado trabajando en el proyecto Better Bus para rediseñar el sistema de autobuses en el Condado de Miami-Dade, Florida, en colaboración con el grupo de interés local Transit Alliance. Este es un caso inusual ya que Transit Alliance está usando fondos recaudados para pagar por gran parte del proyecto, aunque Miami-Dade Transit ha sido un miembro activo del equipo desarrollando un plan que ellos pueden implementar.

El plan borrador de la Nueva Red ya se publicó y está listo para recibir comentarios del público. Puedes leer el informe completo aquí. Esta Nueva Red se diseñó considerando los comentarios que recibimos del público en la fase de los Conceptos el otoño pasado. Siguiendo los resultados encontrados en este proceso de participación ciudadana, la Nueva Red refleja un cambio en el balance entre más frecuencia y cobertura, resultando en más servicio de alta frecuencia (que aumentaría el número de usuarios). Esta Nueva Red se creó en conjunto con Transit Alliance, el Condado, empleados municipales, y en particular empleados de las Ciudades de Miami y Miami Beach, quienes han ayudado a guiar el rediseño de los trolleys municipales.

El periódico local, el Miami Herald, publicó un buen artículo sobre la Nueva Red y las mejoras principales que afectan positivamente a la mayoría de la comunidad de Miami-Dade. Si vives en Miami-Dade, deberías revisar la Nueva Red y tomar la encuesta antes del 31 de marzo.

Previamente, publicamos un Informe de Opciones que destacaba una de las mayores deficiencias del sistema actual, la falta de una red frecuente. La Nueva Red crea una red más frecuente en las partes más densas del sistema a través de la consolidación de rutas muy cercanas unas de las otras, cambiando la función entre algunas rutas del condado y los trolleys (especialmente en la Ciudad de Miami) y algunas reducciones en cobertura, particularmente en municipios que ya tienen servicio de trolley.

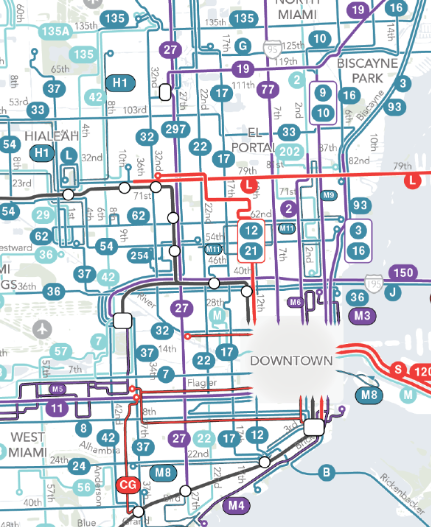

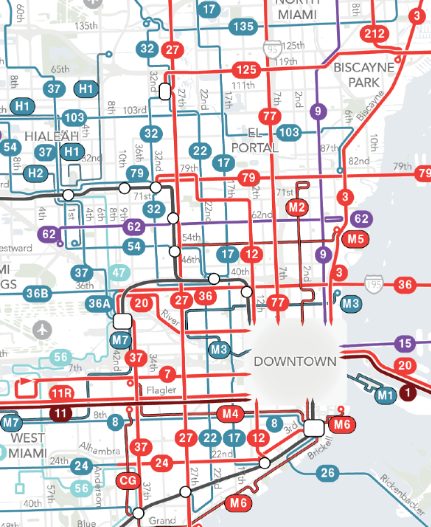

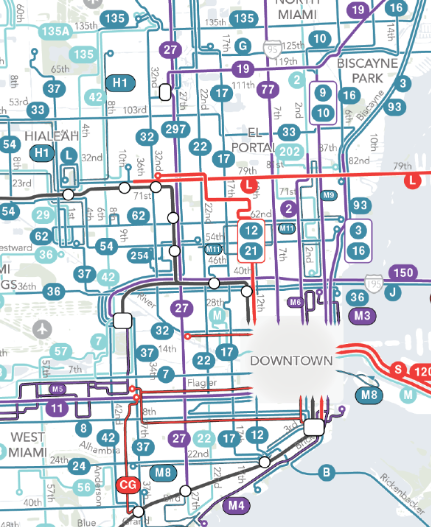

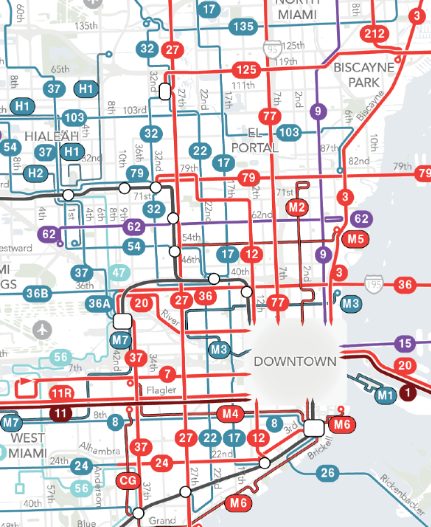

A continuación podrás ver unas secciones de la Red Existente y la Nueva Red en el centro de la región (haz clic para ver los mapas completos de ambas redes).

la Red Existente

la Nuvea Red

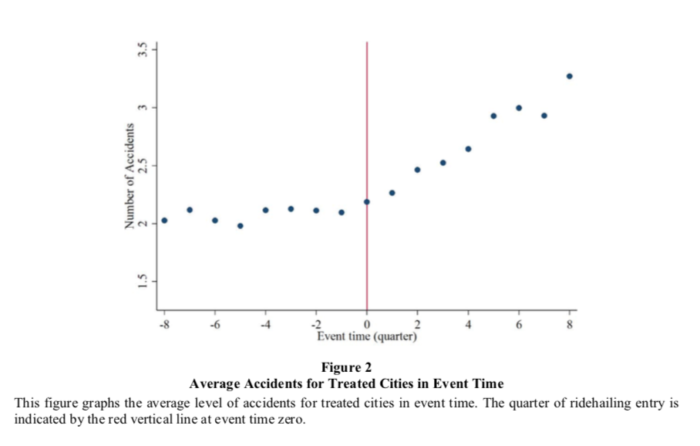

En esta nueva red, 368,000 residentes más están cerca de una ruta frecuente, lo cual hace que el número total de personas cerca de servicio frecuente suba a 25%. En la Red Existente, solo 11% de los residentes viven cerca de una ruta frecuente.

El poder de la red frecuente significa que hay una expansión significativa en los lugares a donde la gente puede ir dentro de un tiempo razonable. A continuación, hay una animación que compara los lugares a donde una persona en Liberty City (NW 12th Avenue and 62nd Street) puede llegar en 45 minutos en transporte público y caminando. La zona gris muestra a donde una persona puede ir hoy, con al Red Existente. La zona azul claro muestra a donde una persona puede ir con la Nueva Red. La red frecuente en la Nueva Red provee una expansión muy grande a tu libertad si vives aquí. Podrías acceder a 60% más oportunidades (trabajos y servicios) y 55% más personas.

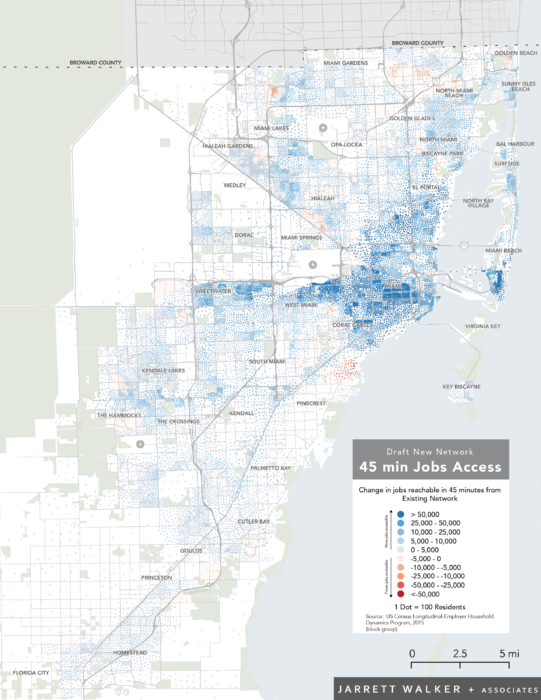

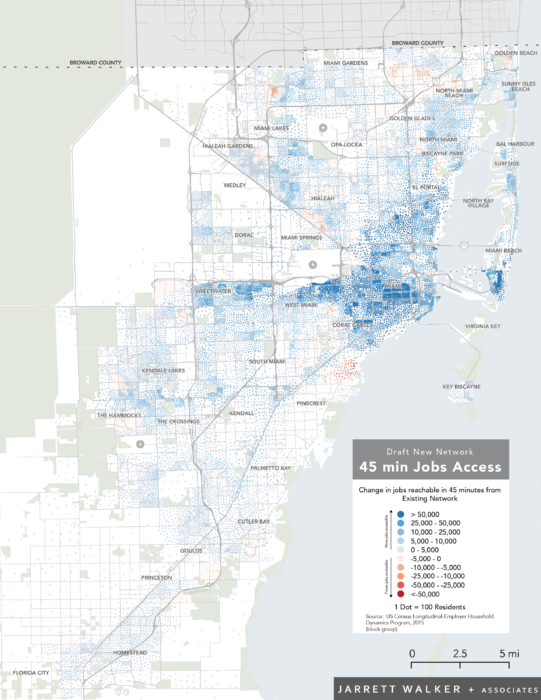

Podemos evaluar este cambio para todas las personas y todos los lugares del condado. El resultado se muestra en el próximo mapa. Las zonas azules muestran en donde la gente puede acceder a más trabajos y las zonas rojas en donde la gente puede acceder a menos trabajos con la Nueva Red. Cada punto en este mapa representa 100 personas.

El mapa muestra que la gran mayoría de la gente y los lugares ven un grande aumento en el número de trabajos accesibles. El promedio a lo largo de todo el condado muestra que el residente típico del condado puede acceder a 33% más trabajos en una hora de viaje con esta Nueva Red.

Estas mejoras son parte de compromisos dolorosos. Esta red enfatiza más las metas de alta frecuencia que la Red Existente. Por lo tanto, algunas rutas de baja productividad con metas de proveer cobertura se han eliminado para poder proveer más servicio en lugares que son más densos, caminables, y lineares. Aproximadamente 3% más de los residentes estarán a más de ½ milla de servicio con la Nueva Red.

La Nueva Red cuesta lo mismo que la Red Existente y es completamente implementable dentro de seis a nueve meses, pero esta red no se implementará antes de que el público, las partes interesadas, los usuarios, y otros interesados, tengan la oportunidad de revisar estos cambios y comentar. Por lo tanto, lee y dile a Transit Alliance lo que piensas.

Si estás de acuerdo que esta Nueva Red será una beneficiosa para Miami-Dade, es importante que lo digas porque mucha gente que se beneficiará con este plan no estará prestando atención y no lo dirá. Si no te gusta este plan, por favor déjale saber a Transit Alliance y a MDT como se puede mejorar. Pero recuerda, cualquier cambio se debe hacer manteniendo un presupuesto neutro. Por lo tanto, aumentar el servicio en un lugar significa que hay que quitar servicio en otro lugar. Siempre recibimos buenísimas ideas de los comentarios públicos en esta fase.

También es importante pensar más allá de los usuarios actuales y pensar en todos los otros intereses que se beneficiarán. Una expansión grande en el acceso a empleo, servicios, y comercio en el condado. Empresas pueden ver como el plan mejora el acceso a sus empleados y clientes. Finalmente, a todo el mundo que le importan los beneficios del transporte público – económicos, ambietales, o sociales – le debe importar lo que este plan puede lograr.

Finalmente, como consultores, nosotros no decimos que este es todo el servicio que el condado necesita; esto es solamente lo que el condado y las ciudades pueden pagar ahora. Claramente hay lugares donde inversión adicional en el servicio podría mejorar el acceso a miles de personas. Algunas ideas de donde se puede mejorar el servicio están documentadas en el Informe de la Nueva Red, como aumentar la frecuencia de servicio en las rutas de 20 minutos en al Nueva Red (Rutas 9, 62, 88). También, la mayoría de la red frecuente se reduce a 20 minutos los domingos. En una región con tanta actividad turística, el servicio de los domingos debe ser más como el servicio de durante la semana y los sábados.