The New York Times today bewails the loss of Los Angeles bus line 305, which soon will stop running diagonally across the city's grid, from Watts to Beverly Hills and Westwood.

NYT reporter Jennifer Medina assumes this is purely a victimization-of-the-poor story, starting with this observation:

The 305 was one of several lines created under the consent decree, and it is the only direct route from the city’s impoverished southern neighborhoods to its affluent West Side, where legions of janitors, nannies and maids work each day.

Sounds sad, and it's easy to fill an article with interviews with 305 riders who will experience the deletion as a hardship. But as that paragraph should warn us, 305 was a symbolic service. It cannot have been relevant to very many people, not even to many people in the targeted demographic ("janitors, nannies, maids" according to the NYT). Why? If you explore the route and schedule [ Download PDF ] and look at how the route fits into the larger network ("System map overview" here), you'll notice:

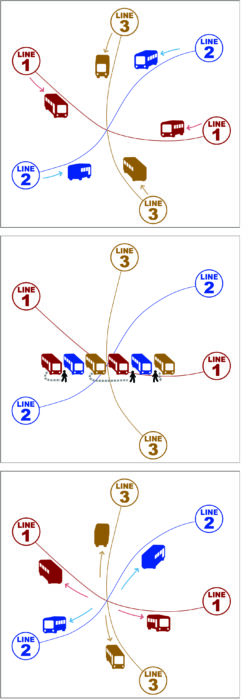

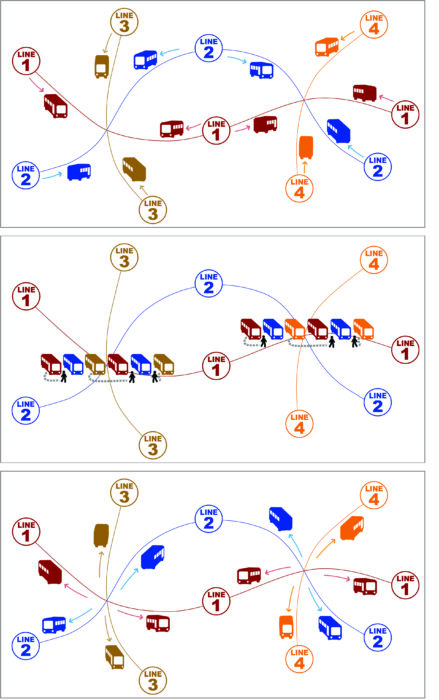

- Line 305 is a diagonal shortcut across a high-frequency grid, where trips between anywhere and anywhere can usually be made on lines running every 15 minutes or better with some are far more frequent than that. Meanwhile, the Line 305 frequency is every 40-60 minutes. [PDF] That means that the 305 is the fastest path between two points on the line only if it happens to be coming soon. If you just miss one, there's another way to get there faster, via the much more frequent lines that flow north-south and east-west across this entire area.

- The 305's low frequency exposes its riders to the risks of waiting for a single bus: you're basically making an appointment with one driver who may not show up for a variety of reasons. Routing the same trips via the high-frequency grid means much higher reliability, because the abundance of buses along a line means you are less dependent on any one of them.

- Most important, the alleged target demographic — trips from the "poor south" to the "affluent west" for domestic workers — was mostly not served by the 305. Both the "poor south" and the "affluent west" are enormous areas. So no one bus line was ever going to connect all or even most of the "poor south" with all or even most of the "affluent west."

These points, but especially the last, identify a public transit service as symbolic. Symbolically, the 305 links the "poor south" and the "affluent west," and thus helps everyone feel good about having served domestic workers. In fact, the 305 runs through a small part of the vast "poor south" and a small part of the vast "affluent west," but it's still useless for most of the people making that kind of trip, because both areas are so large that no one bus line, or even five, could link all of the likely origin-destination pairs between them.

(You could take other buses in each area and transfer to the 305, but the low frequency of the 305 makes this very risky. Once you've accepted the need to connect, you might as well ride along the main grid and connect with a high-frequency line to take you where you're going.)

This problem is why frequency and connections were invented. The governing principle of transit in these core parts of Los Angeles is the high-frequency grid, which allows everywhere-to-everywhere travel at high frequencies with at most one connection. Yes, it may be sad that some domestic workers who are used to zero-transfer trips are now going to have a one-transfer trip, but that only means that 305 riders will have the same level of transit mobility that everyone else has, including most domestic workers. It also means that Los Angeles transit will be treating all of this demographic equally, rather than arbitrarily preferring people whose path happens to lie along Line 305.

The other moral of this story is even simpler: If your mission is to serve a whole city or region, designing transit routes around any self-identified group of people is almost always a bad idea. Most successful and attractive transit seeks maximum versatility, by serving the most diverse possible range of demographics, trip purposes, and origin-destination pairs. You can make exceptions where a single demographic group produces sufficiently massive ridership, as in some commute markets. But in general, the way people self-organize and self-identify politically is a bad guide to how to meet their transit needs efficiently. Everyone can draw the perfect transit line just for their interest group, but such proposals tell you nothing about what a good transit system would look like.

Nobody should be happy about the severe cuts being imposed on many US transit agencies that urgently need to move in the opposite direction. But as in San Francisco in 2009, cuts are sometimes an opportunity to delete services that have passionate, well-connected defenders, but that simply don't make sense if your goal is a complete network that people can use to go wherever they're going.