On Saturday, July 27 (tomorrow as I write this) I’ll be speaking at the opening of a show of my late mother’s artwork. Details here.

General

Miami: The Better Bus Project Goes Public

We’re delighted to announce the release of our analysis of the bus network of Miami-Dade County, the Better Bus Project Choices Report. The report reviews existing services, identifies possible paths for improvement, and also points to difficult choices that policymakers need to think about. Here’s the Miami Herald‘s coverage.

We’ve worked on a lot of bus network redesigns, but the Miami-Dade Better Bus Project is unusual in a number of interesting ways.

Most remarkably, the project is led not by the transit agency, but by a well-resourced and well-respected advocacy group, the Transit Alliance. These folks brokered a deal where they would manage a study on behalf of both Miami-Dade Transit and several of the key cities. They are handling all of the public outreach and government relations, leaving us to just do the planning behind the scenes.

The role of the cities is also unusual. Many cities in the county run their own “trolley” services, which offer small buses, free fares, but often routes that duplicate what the countywide Miami-Dade Transit network does. This happens in other metro areas, but in this project we some of the key cities at the table, trying to come up with the best solution for the city andthe region.

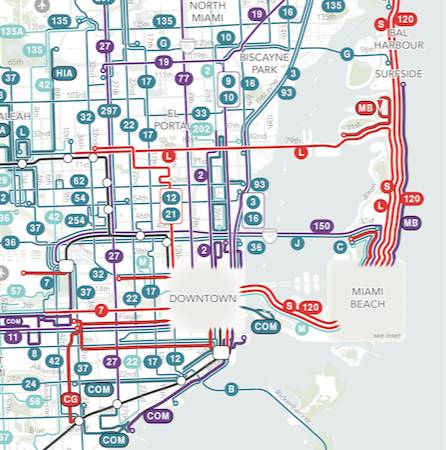

Less unusual, sadly, is now thinly the service is spread. Here’s a bit of the network map for the dense core of the region.

And the legend:

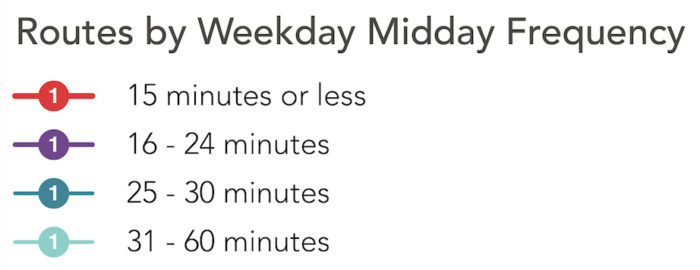

Most effective transit systems have some kind of frequent grid, where many intersecting lines run at least every 15 minutes all day. Houston’s, which we helped design, looks roughly like this:

The key idea of a frequent grid is that wherever red lines cross it’s easy to change buses to go a different direction, and that’s the key to being able to get to lots of places in a reasonable amount of time.

You’ll find extensive frequent grids in a number of gridded cities, including not just big cities like Los Angeles and Chicago but also in Houston, Portland, Phoenix and even Tucson.

But Miami-Dade, which is equally dense and equally gridded, has essentially no frequent grid. There are grid lines, but most run every 20-30 minutes, not enough for connections to be easy. Only in Miami Beach will you find the intensive frequent service that means transit is there whenever you need it.

So that’s one issue we’ll be looking at. Others raised by the choices report include:

- What’s the ideal division of labor between county transit and municipal services?

- Is there too much peak service and not enough all-day service? Overall, productivity (ridership / service quantity) is lower during peak hours than midday, which suggests that might be the case.

- And biggest of all, how should the region balance the competing goals of ridership and coverage?

In the next round of the project, we’ll present illustrations of how the network might look if the region gave a higher priority to ridership, or if it gave a higher priority toward coverage. As always, the first will have fewer and more frequent lines, but less service to some low-demand places, while the coverage network will go everywhere that people expect service, at the expense of lower frequencies. As always, we’ll encourage a public conversation about this unavoidable question.

So if you know anyone in Miami-Dade County, send them to the project website to explore and express their views. Encourage them to peruse the Choices Report. And if you’re interested in reforming bus networks in general, this one will be an interesting example.

Portland: Facing the East-West Chokepoint

That red line (and the adjacent blue line that’s hard to see) is the east-west spine of Portland’s transit system. On the west, it is one of just two direct paths (street or transit) across the hills linking downtown and the the “Silicon Forest” suburbs to the west. But the slow operations across downtown makes this line much less useful than it looks. Credit: Travel Portland.

In 1986, Portland opened one of the first modern light rail lines in the US, the beginning of a light rail renaissance that built networks in mid-sized cities across the country. It was nice to be a leader — we’re used to that in Portland — but it also means that everyone has learned from our mistakes, while Portland still has to live with them.

Perhaps “mistake” is too strong a word, but the priorities of the early light rail designers certainly aren’t the priorities today. Planners of the 1970s (when I was an enthusiastic teenage transit geek) confronted a city whose downtown consisted mostly of surface parking while prosperity fled to the suburbs. Their top priority wasn’t even getting people to downtown. It was making downtown a place worth going.

So they built a line that rushes into the city from the eastern suburbs, but then creeps across the inner city, making lots of stops for a net speed under 7 miles/hour. For a while that was fine. All those stations meant lots of development sites right next to the line, and downtown grew and prospered.

Today, the success at revitalizing downtown has created an opposite set of problems. Downtown and the surrounding neighborhoods are so successful that working people can’t afford to live there. Low income people are being pushed out to places where they face longer commutes. Most important, the line now continues west out of downtown to serve the “Silicon Forest” suburbs to the west, so that it runs across downtown, not just into it. Meanwhile, the development that the slow downtown segment was supposed to stimulate is largely done.

So the downtown segment of the line is becoming more of a barrier than a resource.

Transit in Portland benefits enormously from chokepoint geography. Between the inner city and the western suburbs, there is a wall of hills pierced by one gridlocked freeway, one parallel arterial, and a light rail line. This rail segment has prospered because the driving alternatives are terrible.

As always, chokepoint geography means: It’s worth spending a lot of money improving transit here, because so many trips, between so many places, go through this point. A regional inbalance of jobs and housing (more jobs in the west, more housing in the east) has create a huge east-west travel demand right through this ch0kepoint. The hills are still a barrier for drivers, but for transit the barrier is the slow downtown streets, and the 1970s assumption that the train needs to stop near every building.

As if the slow operations weren’t bad enough, there’s also a problem of capacity. Portland’s adorable little 200-foot blocks, rightly credited with giving downtown such a human scale, limit the train lengths to 2 cars as long as they run on the surface. The city is too big now, and its transit needs too dire, for such tiny trains to do the job.

The problem is being attacked at several scales. The transit agency is gingerly suggesting that a few stations should be closed. Stations on the downtown segment are as close as 350 feet — far too close for bus stops, let alone rail stations. (The newer north-south light rail line, whose designers learned from the mistake, has station spacing closer to 1000 feet. Unfortunately, it is the east-west line that extends furthest into the suburbs and therefore serves the most people.)

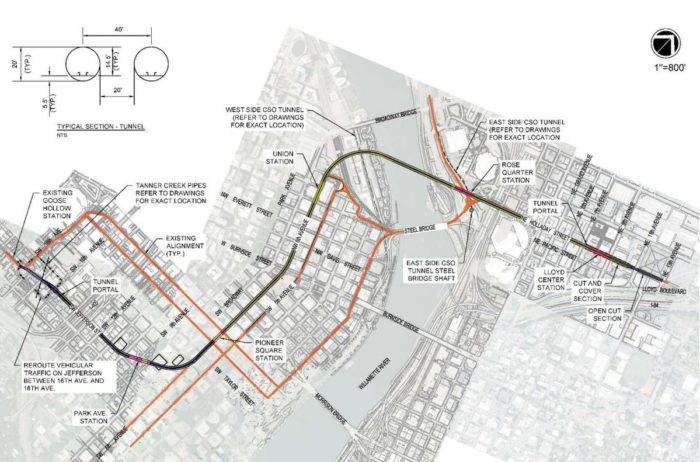

But the problem is so big, and obstructs so much access to opportunity across the region, that it won’t be solved just with half measures. A long overdue study is looking at the complex of capacity problems, and while it’s looked at some half-measures, the only thing that solves all the problems is a new segment of subway under the core. The long frequent east-west lines serving suburbs (and the airport) would go into a tunnel, rushing under downtown in perhaps 1/3 the time, so that transit would finally be viable for travel across downtown and not just to it. The existing surface line would still be used to provide a more local service across downtown.

An early concept for the downtown rail tunnel (black) with existing light rail segments in red. The tunnel has six stations counting the endpoints. Too many?

I have been skeptical of many rail projects in my time, but the most defensible of all are these “core capacity” projects. Like the excellent Los Angeles Regional Connector, this is a project that is in downtown but not for downtown. Its purpose is to unlock the potential for all kinds of access across the region. To bypass the inevitable edge-core debate, it will have to be presented in those terms.

That’s why I’m a little skeptical of the earliest concepts. As sketched the tunnel has six stations downtown. They should at least study a line that just has three: the two edges of downtown — Lloyd Center and Goose Hollow — where the fast line would connect with the slow surface line, and just one station at the very center of the city, Pioneer Courthouse Square, where almost all of they city’s radial transit services meet. This would make the new line barely half as long and much less expensive.

Obviously there are great arguments for every proposed downtown station: the university, the stadium, the train station. But it’s going to be important to have clear conversations about the balance between downtown and regional benefit, and between the benefits to an already prosperous downtown and the need for reasonable travel times for low income people, who are increasingly pushed further out where they have to travel further.

I don’t know that a three-station solution is right, but I know it should be looked at. It’s really easy to get around downtown on transit, from anywhere to one of the three stations that this minimal version would offer. It’s really hard to get across the region, and every station we add to this project moves us back toward not solving that problem — not just by making the line slower but also by making it more expensive. It’s a tough balance, and I hope we’ll have the debate.

Chattanooga: Choices for the City’s Transit Future

Chattanooga Incline Railway

Chattanooga, Tennessee’s most well-known transit infrastructure may be the Chattanooga Choo-Choo, a former train station made famous by a 1941 swing tune by Glenn Miller and His Orchestra, or perhaps the Lookout Mountain Incline Railway, a tourist-oriented funicular currently owned and operated by the Chattanooga Area Regional Transportation Authority (CARTA). Most days though, Chattanooga’s transit line with the highest ridership is the Route 4 bus from downtown to the eastern suburbs. Although Chattanooga was an early adopter of electric buses, starting their downtown electric shuttles in 1992, transit has not been at the forefront of its planning policies in the past few decades. Like many other similarly sized cities without urban growth boundaries in the US, development has sprawled outwards, enabled by highways, resulting in land use patterns that are difficult to serve by transit.

That is changing. In recent years, Chattanooga has focused efforts on rekindling the inner city, adding housing, retail, and office space downtown, and becoming the first midsize city in the US to designate an urban innovation district. As a recognition of their efforts to build vibrant public spaces, Chattanooga will be hosting the Project for Public Spaces placemaking conference this Fall, the third city to do so after Amsterdam and Vancouver. But in order for a city center integrated within a growing regional economy to scale up without being choked by traffic congestion, Chattanooga needs better transit. Today, the city is starting to reconsider the role of the bus and may be ready to make major changes to its bus services and perhaps invest more in it.

The recently revamped Miller Park in Downtown Chattanooga. Photo: downtownchattanooga.org

We’ve been studying the transit system in Chattanooga for over a year and in June CARTA released our report outlining four possible concepts of what the future of transit could look like. These four concepts show a range of options between coverage and ridership goals with no new funding and two options with additional funding for transit. Happily, the local newspaper’s coverage is clear and accurate.

The release of this report begins the period of public discussions and surveys. The results of that discussion will inform the decision that the CARTA Board makes in August about what direction the final plan should take.

Our report discusses four possible futures but most likely, the final plan won’t look quite like any of these. The key idea — as in much of our work — is to open up a “decision space” in which people can figure out where they want to come down on the two difficult policy decisions:

- Ridership vs coverage? What percentage of resources should to go pursuing a goal of maximum ridership — which will tend to generate frequent service in the densest urban markets — as opposed to the goal of coverage — spreading service out so that as many people as possible have some service nearby?

- Level of investment in service? How much should the community invest in service? The more it invests the more it gets in value, but the value it gets depends in part on how you answer the ridership-coverage trade-off.

If you live in Chattanooga or know anyone there, now is the time to get involved. Download the report, read at least the executive summary, form your own view, and share it with us here! The more people respond, the more confident we’ll be in defining the final plan based on their guidance.

A Walk in a Very Small Town

Over on the personal blog, I took a walk in Lineville, Iowa, and sold some real estate there for $200 (US).

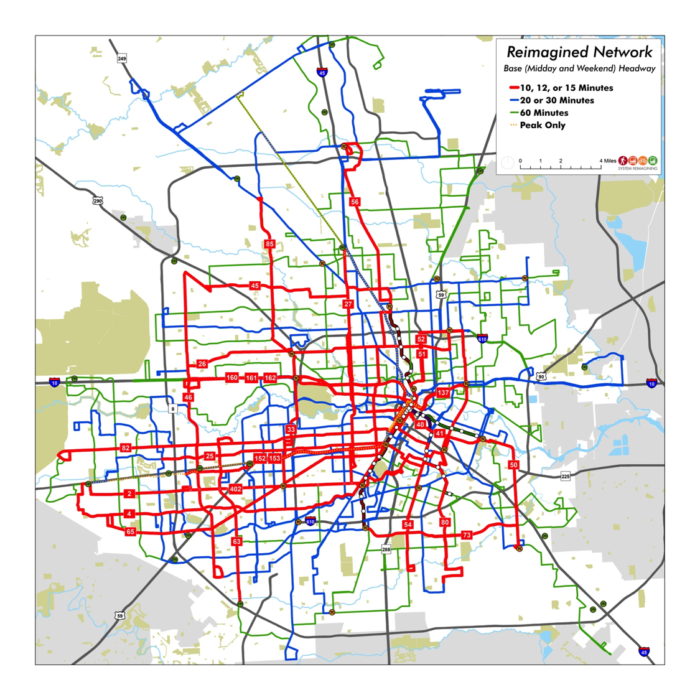

Mirra Meyer, 1942-2019

My mother, the artist Mirra (Louella) Meyer, passed away on Friday, April 16. The story of her life, with images of her work, are here.

Do Uber and Lyft Want to Connect to Transit?

Uber and Lyft — especially Lyft — want you to think that they are partners of public transit, eager to help more people get to rapid transit stations. Lyft and Uber have both created partnerships with transit agencies to provide “last mile” service. When people talk about the “last mile” problem of access to transit (a problem that exists mostly in suburban areas or late at night) Lyft and Uber are eager to seem part of the solution.

I would like to believe this. Here are two reasons I don’t.

Uber/Lyft Drivers Don’t Want Short Trips

First, no Uber or Lyft driver really wants to offer a “last mile” because a mile is too short a trip to make sense to them. The hassles of each trip are constant regardless of the trip’s length, so long trips are always preferred. In the old days of taxis, whenever I booked a taxi ride to a transit station, the driver always pitched me to give me a ride all the way to my destination. And if I approached a long taxi queue at a suburban rail station and told the driver I wanted to go a mile, he’d be unhappy to say the least, because he spent a lot of time waiting for my fare.

That’s why the partnerships between Uber/Lyft and transit agencies for “last mile” service inevitably involve public subsidy, which means that they compete with other kinds of transit service for those funds. (This can be OK if transit agencies have really decided that this is the best use of funds given all of their other needs.)

2. Uber/Lyft Drivers Can’t Find Transit Station Entrances

Uber and Lyft drivers mostly use mapping software that can’t find many transit station entrances. If connecting with transit were a critical part of their business, this would have been fixed by now.

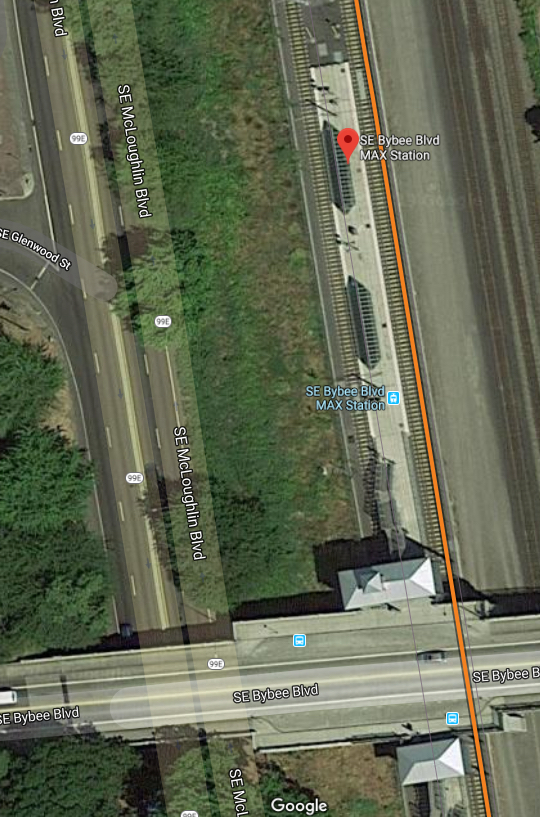

The nearest rapid transit station to my home in Portland (Bybee Blvd) looks like this:

This is a typical suburban arrangement (although this is not really suburbia). The station is alongside a highway (labeled McLoughlin Blvd.). The pedestrian access to the station is from the overpass. The little roofs are the elevators and stairs.

But the mapping apps think that the station entrance is on the highway.

So it is impossible to call Uber or Lyft to this station, because the software tells the driver to go down the highway, where all they’ll find is a fence. I can text them to correct it, but not all drivers pay attention to texts (nor should they, while driving.) And even if I correct it, I’ll then wait an extra 10 minutes as they get themselves turned around and navigated to the right spot.

This is the example I deal with all the time, but I’ve found many suburban rail stations in many cities where drivers don’t have clear directions about station locations. For example, call Lyft or Uber to Van Dorn Metro Station in Alexandria, Virginia, and you can expect the driver to wander all over the adjacent interchange.

Some people clearly need to go to work accurately coding the location of every entrance to every transit station, but it’s clearly not being done. Why not? It must not be that important to these companies.

So Do Uber and Lyft Want to Go to Transit?

It makes sense that Uber and Lyft would want to do long trips to rapid transit, more than a few miles. For example, in San Francisco, Uber and Lyft do a good business to regional rapid transit stations (BART and Caltrain) but since each system has only one line in the city, these can be trips of several miles (often competing with the abundant local bus and light rail system).

And Uber and Lyft certainly want to be subsidized to do more “last mile” work, via partnerships with transit agencies.

But the drivers’ inability to find transit station entrances — and the fact that this problem has been tolerated for years — is what really decides it for me. Companies that really want to connect with transit would have made sure that they can navigate a driver to any entrance of any rapid transit station. But they don’t.

Why Invest in Lyft or Uber? What Am I Missing?

Lyft has completed its Initial Public Offering, and at this writing the price has since fallen 35%. Uber’s IPO is expected soon. Both will now be publicly traded companies, reliant on many people’s judgments about whether they can be good investments. Uber loses billions of US dollars every year, while Lyft, which is smaller but growing faster, is getting close to losing $1 billon/year for the first time.

Why invest in these companies?

Anyone who says “Amazon lost money too at first” is just not thinking about transportation. Amazon can grow more profitable as they grow larger, because they can do things more efficiently at the larger scale.

Uber and Lyft are not like this, because their dominant cost, the driver’s time, is entirely unrelated to the company’s size. For every customer hour there must be a driver hour. Prior to automation, this means that no matter how big these companies get, there is no reason to expect improvement on their bottom line. Any Uber or Lyft driver will tell you that these companies have cut compensation to the bone, and that they already require drivers to pay costs that most other companies would pay themselves, like fuel and maintenance.

If Uber and Lyft could rapidly grow their shared ride products, where your driver picks up other customers while driving you where you’re going, that could change the math. But shared ride services don’t seem to be taking off. My Lyft app rarely offers me the option, even when I’m at a huge destination like an airport, and when they do it isn’t much of a savings, which suggests that it’s not really scaling for them.

Of course Uber and Lyft could also go into another business, such as bike and scooter rental, but in doing that they’re entering an already crowded market with no particular advantage apart from capital. The single-customer ride-hailing is the essence of why these companies exist, and there’s no point in investing in them unless you think that product can succeed.

Please correct me if I’m wrong, but it seems to me the possible universe of reasons someone would invest in these companies is the following:

- Confusion about the basic math of ridehailing, outlined above. Hand-waving comparisons to Amazon are a good sign that this mistake is being made.

- Extreme optimism about Level 5 automation, which would indeed transform the math by eliminating drivers. I no longer hear many people saying that commercial rollout of Level 5, in all situations and weathers, is imminent, as many people believed around the time Uber and Lyft were founded. (And no, it makes no sense to have a huge crew of drivers ready to take the wheel only when the weather looks bad. Nobody can live on that kind of erratic compensation.)

- A naive belief that if you love a product, or find it essential to your own life, it must therefore be a good investment (a rookie investing mistake).

- A belief that while you don’t believe any of those three things, enough other people do that those people will drive the price up, and you can get out before they discover the truth. If this goal were intended clearly and honestly, it would be Ponzi scheme. So surely it can’t be that.

So I must be missing something. What am I missing?

Orlando: Speaking on Thursday, March 14

The Orlando Economic Partnership‘s Alliance for Regional Transportation has invited me to speak at a lunch event this Thursday, March 14. Admission is $40, but they apparently feed you. Details and registration here.

The Orlando Economic Partnership‘s Alliance for Regional Transportation has invited me to speak at a lunch event this Thursday, March 14. Admission is $40, but they apparently feed you. Details and registration here.

Cleveland: Kicking Off a Transit Plan

I’m just back from a week in Cleveland, where I introduced our new transit planning project to members of the transit agency board and began the process of working with staff to develop network concepts that will help the public think about their choices. Press coverage of my presentation is here, here, and here. The local advocates at Clevelanders for Public Transit are also on the case.

Cleveland is in a challenging situation. The city has been losing population for years and most growth has been in outer suburbs that were designed for total car dependence. Low-wage industrial jobs are appearing in places that are otherwise almost rural, requiring low-income people to commute long distances.

All this is heightening the difficulty of the ridership-coverage tradeoff. The agency faces understandable demands to run long routes to reach remote community colleges and low-wage jobs, but because these services require driving long distances to reach few people, they are always low-ridership services compared to what the agency could achieve if it focused more on Cleveland and its denser inner suburbs. There’s no right or wrong answer about what to do. The community must figure out its own priorities.

To that end, we have helped the agency launch a web survey to help people figure out what the agency should focus on. In April, we’ll release two contrasting maps that illustrate the tradeoff more explicitly, and again ask people what they think. Only then will we think about developing recommendations.

If you live in Cuyahoga County, please engage by taking the survey!