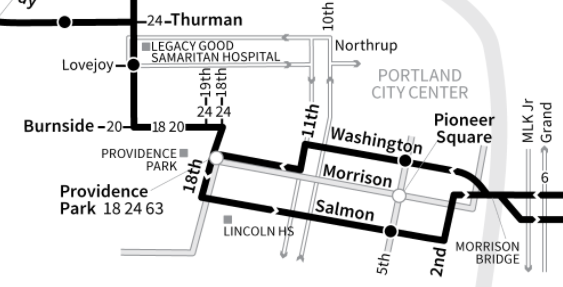

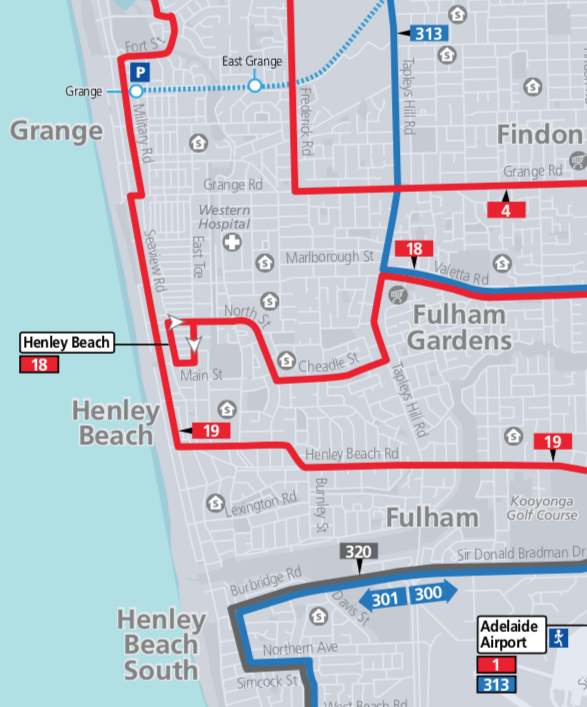

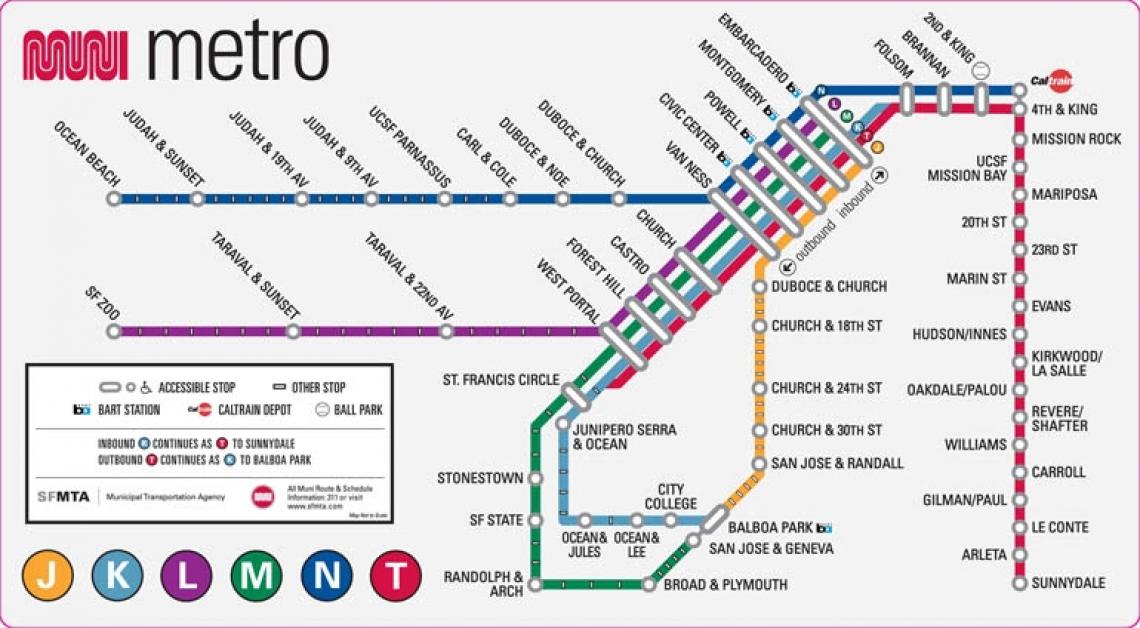

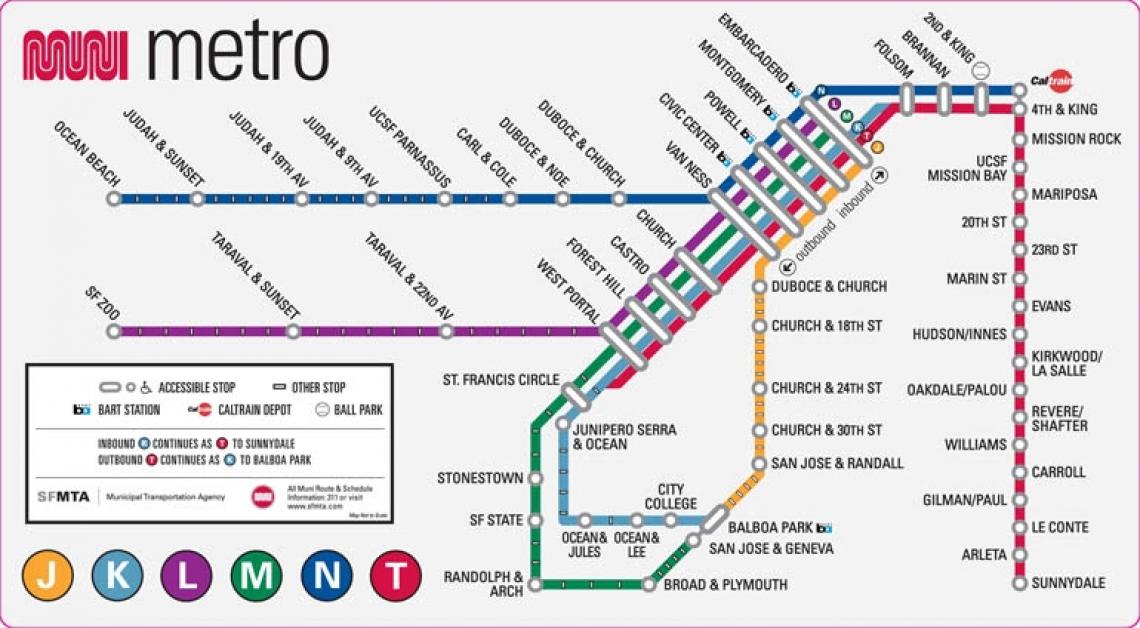

Around 1989, when I lived in San Francisco, I spent too much time in little rooms with transit advocates (and some transit professionals who could not be named) complaining about Muni Metro, the combined surface-subway light rail system. It looked like this and still does, except that the T line was added more recently. Note the r0ute letter names in the lower left.

The segment with 3-5 lines on it, from Embarcadero to West Portal, is the underground segment, which carries the heaviest loads through the densest part of the city.

It had always been wildly unreliable. The five lines that ran through it (J, K, L, M, and N) always came in sequences of pure arithmetic randomness: N, J, M, K, J, N, N, K, K, M, N, J, L. (Finally, my “L”! But of course, after such a long gap, it’s crush-loaded and I can’t get on.)

Four decades after the subway opened, lots of things have been fixed: longer and better trains, better signaling, an extension downtown that helped trains turn back more efficiently. But none of this touched the true problem: The core Metro subway carries five lines, all of which deserve to be very frequent. But they can’t all be frequent enough because they all have to squeeze into one two-track subway. The other part of the problem is that they all have surface segments at the outer end, where they encounter more sources of delay, causing them to enter the subway at unpredictable times, and in an unpredictable order.

In those small rooms in the 1980s, we all knew that there was only one mathematically coherent solution. Some us drew the map of this solution on napkins, but we really didn’t need to. The map was burned into our minds from our relentless, powerless mental fondling of it. Of course it was politically impossible, so impossible that if you valued your career you would wad up that napkin at once, burn it probably, and certainly not mention it outside your most trusted circle.

At most you might let out the pressure as a joke: “You know, we *could* turn the J, K, and L into feeders, and just run the M and N downtown. And then we’d have room for a line that just stayed in the subway, so it was never affected by surface delays.” Everyone would titter at hearing this actually said, as though in some alternate universe such a change could be possible.

Now, the impossible is happening. Without fear or shame, I can finally share the content of that forbidden napkin, because it looks like San Francisco is actually going to do it.

The two busiest western lines (M, N) will still go downtown, the others (J, K, L) will terminate when they reach a station but you have to transfer to continue downtown. M trains will flow through as T. Finally, a shuttle (S) will provide additional frequency in the subway, immune to surface delays. As always, asking people to transfer makes possible a simpler, more frequent, and more reliable system.

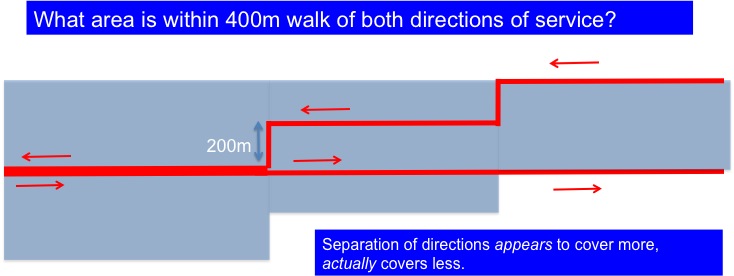

You may detect, at San Francisco’s tiny scale, a case of the universal “edge vs core” problem. Like many, many US rail transit systems, Muni Metro had been designed to take care of the edge, people who lived on one of the branch lines, rather than the core, people traveling along the subway in the dense inner city. The new system finally fixes the core. But the edge folks benefit from a reliable subway too. What’s more, in the future it may be possible to run the surface segments of J, K, and L more frequently, because their capacity will no longer be capped by the need to fit down the subway with four other lines.

All that in return for having to transfer to go downtown if you’re on the J, K, or L.

Let me not make this sound easy. These transfer points, West Portal and Duboce Portal, are a little awkward, because they were never designed for this purpose. You have to walk from one platform to another, crossing at least one street. There are valid concerns from people with mobility limitations, which will have to be addressed with better street and intersection design. Plenty of people won’t like it.

But the transit backbone of a major city will finally function. And for those of us who’ve known San Francisco for decades, that’s a forbidden fantasy come true.