When you hear the word integration or seamlessness in conversations about transit, it usually means making it easy to make trips that involve multiple public transit agencies or operating companies. (In the US we are generally talking about entangled government agencies, but in countries where private operators control patches of the network, the issue is the same.)

The San Francisco Bay Area has long been one of North America’s most difficult integration challenges, so it’s a good laboratory for exploring the issue. If you can get transit integration right in the Bay Area, you can probably do it anywhere. The Bay Area’s particular challenge is that it has no recognized central city. Instead, it’s named after an obstacle, the Bay, and its geography of bays and hills provides natural psychological divides. Wherever you live in the Bay Area, most of the Bay Area is “across the water” or “over the hills” from you, and this matters enormously to how people perceive issues as local or regional. (Los Angeles, mostly a city of vast continuous basins, could not be more opposite.)

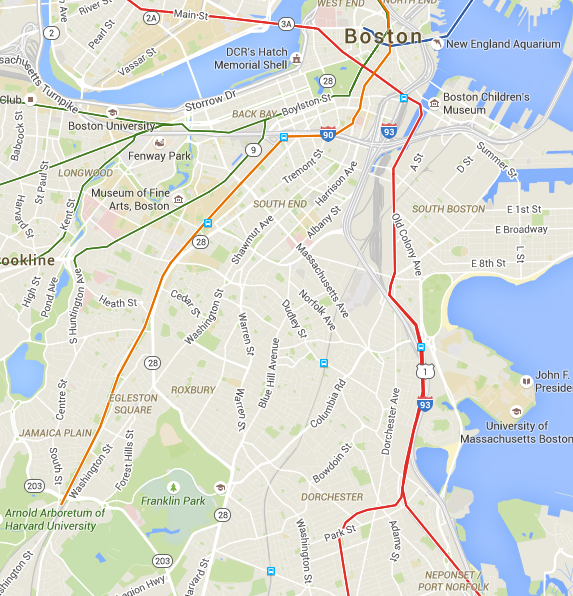

Map of Bay Area transit agencies (SPUR, “Seamless Transit” 2015)

The key types of seam are:

- Fare barriers, where a trip involving two agencies requires paying both agencies’ fares, and sometimes also keeping track of two kinds of ticket or pass.

- Information barriers, such as the lack of a clear map. (In many regions, the only regionwide map, if it exists, is more like a diagram of turf. It’s designed to clarify what agency controls what rather than help people understand their travel options.) Other information barriers include information systems that don’t describe how to use other agencies’ networks to complete common trips.

- Service Design Barriers, where a route ends at an agency boundary even though almost everyone on the bus is trying to go further.

For decades, it’s been easy to propose that some grand merger of agencies would solve problems of integration, but the obvious problem was you would have to merge the whole Bay Area into one transit authority serving almost 8 million people, in a region around 100 miles long. That population would mean little citizen access to the leadership, while the huge area would mean that people planning your bus routes may be working in an office 50 miles away. It just doesn’t work when the sense of citizenship is as understandably decentralized as it is in the Bay Area.

What’s more, if you value transit-intensive core cities, places like San Francisco and Oakland, or if you want your city to be more like those places, you have an especially strong reason to want local control. These places need more transit than the whole region wants on average, so they will struggle to get adequate service from a regional transit agency, whose decisions will tend to converge on the average regional opinion.

Many North American regions are seeing conflict around this issue, and are evolving a fascinating range of solutions. Many of these solutions involve additional funding from the cities that want more transit than the regional average.

Some core cities are proud to have their own city-controlled transit systems separate from what regional agencies do (San Francisco, Toronto, Chicago). Some pay their regional transit agency for a higher level of service in the core city (Seattle, Salt Lake City). Some run their own transit systems overlaid, often messily and confusingly, on the regional one (Washington DC). Many more core cities are going to face this issue soon, especially if regional politics continue to polarize on urban-exurban lines.

Apart from the issue of urban-exurban differences in the need for transit, there are also real challenges when a single transit agency becomes enormous, especially if it provides local service over a vast geographic area. Los Angeles is a great example. As an undergraduate in the 1980s, living in the region, I marveled at what I assumed to be the stupid chaos of provincialism. The region had a big transit agency, which has evolved into what we now call LA Metro, but many cities within the region ran their own transit systems, which were tangled up in each other, and with the regional agency, in complex ways. As an undergraduate, I assumed that progress would mean merging all this into one giant agency that could provide the same product everywhere.

And yet: in those days, everyone hated the regional agency, but loved their city ones. And there were good reasons for that that weren’t anyone’s fault, and still aren’t today. You could get your city’s transit manager on the phone, but not the regional one. Small city governments can fix a bus route and put up a new bus shelter in the time it would take the regional agency to organize the right series of meetings. Again, nobody’s at fault there; these are natural consequences of smallness and bigness — in corporations as well as in governments.

Which is why, even in Los Angeles, the trend is not toward mergers. Today, many city systems in the county are doing excellent work at their local scale. LA Metro has improved massively as well, of course, but its costs are still high; more important, it’s still very big and therefore inevitably feels distant to many people — again, not the fault of the folks working there.

Meanwhile, a clearer negotiated boundary between regional and city functions is slowly starting to emerge. One idea, for example, is that a key role of city systems is to run services that don’t meet regional standards for ridership, but that the locals feel to be important. The division of labor among agencies is not what anyone would design from scratch. But great work has been done over the years to build clearer relationships, or what I will call, later in this post, “good fences.”

City-operated transit is growing more popular in North American for another excellent reason: Most of transit’s ability to succeed is already controlled by city government: specifically the functions of land use planning and street design. If a city government feels in control of its transit, it is more likely to exercise those other functions in ways that support transit rather than undermine it. San Francisco’s recent decision to combine traffic and parking functions with transit under one city agency shows a new way of thinking about the need to get this right, but it would be impossible if San Francisco relied on a big regional agency for its transit service. Whenever someone proposes to turn a city transit system over to a consolidated regional agency, I have to point out that integrating in one dimension (between geographically adjacent services) means disintegrating in another (between key functions of city government.)

So there’s no simple answer. City control creates a nasty patchwork of geographic integration problems across adjacent cities in a region. The big regional agency has a different integration problem, which is with the land use and street design functions of municipal governments that don’t control their transit and therefore have trouble caring about it. Whichever thing you integrate, you’re disintegrating the other.

What’s the answer? It’s for each region to feel its way through the inevitable tensions to its own solution. But I’d propose we start old fashioned idea made famous by a Robert Frost poem:

Good fences make good neighbors.

Neighbors have an easier time being friendly if they have a very clear agreement about where their boundary is. Collaborating with your neighbor to mark the boundary, and fence it if need be, is a peacemaking gesture. This is as true of neighboring landowners as it is of nations. And it’s certainly true of transit agencies.

What does it mean to have a clear sense of boundary?

It’s not just that both sides agree where the boundary is. It’s also that it’s easy for both sides to live with the boundary, and work across it as need be. For nations, it’s much easier to manage a boundary that runs across a natural barrier, so that the natural boundary reinforces the agreed boundary — the Rio Grande River between the US and Mexico, say, or the Great Lakes along the US-Canada border. The worst possible national boundary is something like the 49th parallel, the US-Canada border in western North America, an arbitrary line that runs perpendicular to most mountains and valleys. Only the extreme friendship and cultural affinity between the two countries makes this boundary workable.

All that is true of transit agencies as well. Let’s talk first about local networks, and then, separately, about the relationship between networks of different scales.

Boundaries between Adjacent Local Transit Agencies

A bank of hills or a water body means that there are limited points of access across the boundary, called chokepoints, and this in turn means people are used to going out of their way to cross that point. That means, in turn, that a well-placed transit connection point adjacent to the bridge or pass is an easy place for transit agencies on the two sides to converge.

On the other hand, a boundary that runs across a flat expanse of urban area, so that many people are literally across the street from the other side, is a problematic transit boundary. In this case there is decentralized demand in all directions crossing the boundary at many points. This makes it harder to bring both agencies to a shared focal point for connections between the agencies. It also means there are lots of relatively short trips flowing over the border, and these benefit from a continuous network of service rather than an interrupted one. As in many US states, California transit agency boundaries tend to default to county lines, and where these create that problem, it’s a mess for transit.

Some of this wisdom is already encoded in the boundaries of the East Bay agency AC Transit. Near the Bay, the border between Alameda and Contra Costa counties cuts across dense urban fabric, so it would be an awful place for a transit network to end from the point of view of either side.

Recognizing this, AC Transit was constructed to unite the two sides of the county line where the urban fabric was continuous, while dividing from other agencies along natural hill and water boundaries, even where the latter are not county lines. This is an important example for many US regions where counties are the default planning units, and arbitrary boundaries drawn in the 19th century (or before) risk turning into walls that sever transit access.

For AC Transit, the “good fences” solution was to put the border in a place that worked well for both sides — worked well for transit customers, that is, not for anyone’s desire for turf or empire. That tends to mean looking for the natural chokepoint and putting the boundary there.

This observation also helps to clarify the city transit option. Even in big urban areas, some cities have a geography that makes it easy for much of the transit to be city-controlled, typically because of natural chokepoints along the edges that help isolate the city-scale network from the regional one. On the other hand, if the city boundary is logically pierced by long, straight local transit corridors that logically function both within the city and beyond it, a municipal network is less viable.

Burbank, California is a good example of a city where most main streets are parts of much longer logical lines running deep into adjacent cities, so its city limits would make especially poor transit boundaries. Burbank therefore profits from its reliance on LA Metro, which runs long, continuous lines across city boundaries many of them converging on Burbank’s downtown. The regional network is also, logically, the local one.

Nearby Pasadena (considered together with Altadena) has good geography for a larger city role. It has hill barriers on three sides — only the east edge is really continuous with other dense urban fabric — so fewer of its internal corridors necessarily flow into other cities. (Areas whose density is so low that they might as well be wilderness as far as transit is concerned — San Marino in this case — count as natural barriers to some degree.) Another important feature is that Pasadena has a frequent regional rapid transit line running through, so its local lines don’t need to extend far out of the city to make regional connections.

So Pasadena could run most of its local transit system if it wanted to, because a logical network would consist mostly of internal routes. Burbank could not, because most of its local service is logically provided by routes that continue beyond the city limits.

Do not quote me saying that Pasadena’s transit should be more local. I am not saying anything about what the regional-local balance should be in these cases, but merely observing how the geography makes the opportunities larger or smaller. One value of Pasadena being served by the regional agency, for example, is that it can eventually be part of a larger high-frequency grid, with all the liberty that brings.

Local – Regional Transit Boundaries

All that is about what happens between local networks. But another “good fence” can be a clear division of labor between local and regional services. Regional services that are designed as rapid transit (widely spaced stations for fast operation between them, relying on local transit connections to get closer to most destinations) do not need to be the same agency as the local service meeting them; in fact, this can be a very clean “fence.” Obviously you have to work on the specific problems of integration: information, fares, etc., just as adjacent local agencies do. But there’s little need to merge or change boundaries in these situations.

There will always be seams in a transit journey, just as there will always be the need to make connections. The conversation should not be about how to get rid of seams but how to put them in the right places, so that they work for both sides, and how to manage them so that travelers can flow through them easily.

Another way of thinking about the geographic issues I’ve been laying out here is that if you require a connection to continue your trip, there should be a rich payoff in terms of destinations you can reach. The same is true for any hassles created by seams. It’s like planes: it’s a drag to change planes, and especially to change between airlines, but it’s kind of cool, while you are changing planes, to look at the departure board and think about all the other places you could also get to via this connection. What’s more, all those connections are crucial to making your flights viable for the airline, even if you don’t use them.

The logic of connections is the logic of good seams in general. They happen in places where it already makes sense for transit services to be discontinuous — either because of a natural boundary or because of a clear division of labor between regional and local service. Those “good fences”, once found, can make for happy neighboring transit authorities, which will find it easy to work together for the sake of the customer’s liberty.

Sure, let’s regionalize the right things: fare media, information systems. (An often-neglected one is service change dates, so that timed connections between agencies don’t get broken because the agencies change their schedules at different times.) Some mergers may make sense, such as between BART and Caltrain to create a regional rapid transit agency.

Big transit agencies and little ones are both excellent things. The trick is to get the fence right.

UPDATE: For a book-length academic analysis reaching a similar view, see Donald Chisholm: Coordination without Hierarchy. 1992, UC Press. H/t David King.