Houston’s West Loop Freeway. How many of these lanes were in the national interest?

We all need to practice reading and refuting arguments of the form: “Central government should focus on big national issues, like highways, instead of local needs, like transit.” It’s become one of the most common ways for people to dress up their preference for roads over transit as an expression of a consistent policy.

Here’s how it sounds:

For the most part, transit systems are local matters. Using federal taxes to collect money from the whole country and then send it back to each local transit system is a terribly inefficient way to raise money for transit and is also inherently unfair as different locales receive back either more or less than they paid in. The only reason to rely on federal funding for part of the cost of local transit systems is that it helps local politicians by keeping their local taxes and transit fares lower.

This common practice of using federal funds for local projects in order to hide the true cost should be stopped. The federal government should pay for the things that are truly national in scope (like the interstate highway system). This type of federal spending for local needs encourages too much government spending by making higher costs easier to sell to voters.

That’s University of Georgia economics professor Jeffrey Dorfman, in Forbes yesterday.

Dorfman seems to invoke the principle of devolution — the idea that government actions should be planned and funded at the lowest level of government that can deal with the issue within its boundaries. It’s often stereotyped as a conservative idea in the US, but it shouldn’t be. In the UK, for example, it’s mostly the leftist cities who are rebelling against over-centralization of planning power in Westminster. The same idea is gaining force in US urban policy, as cities chafe under rule by central governments that care only about suburbs and rural areas. Everyone prefers to deal with more local governments that are easier for a voter to influence, so this is a space of potential left-right agreement that deserves more discussion.

But the notion that highways are national while transit is local? This makes sense if you’re a motorist, but here’s what happens when you press on it:

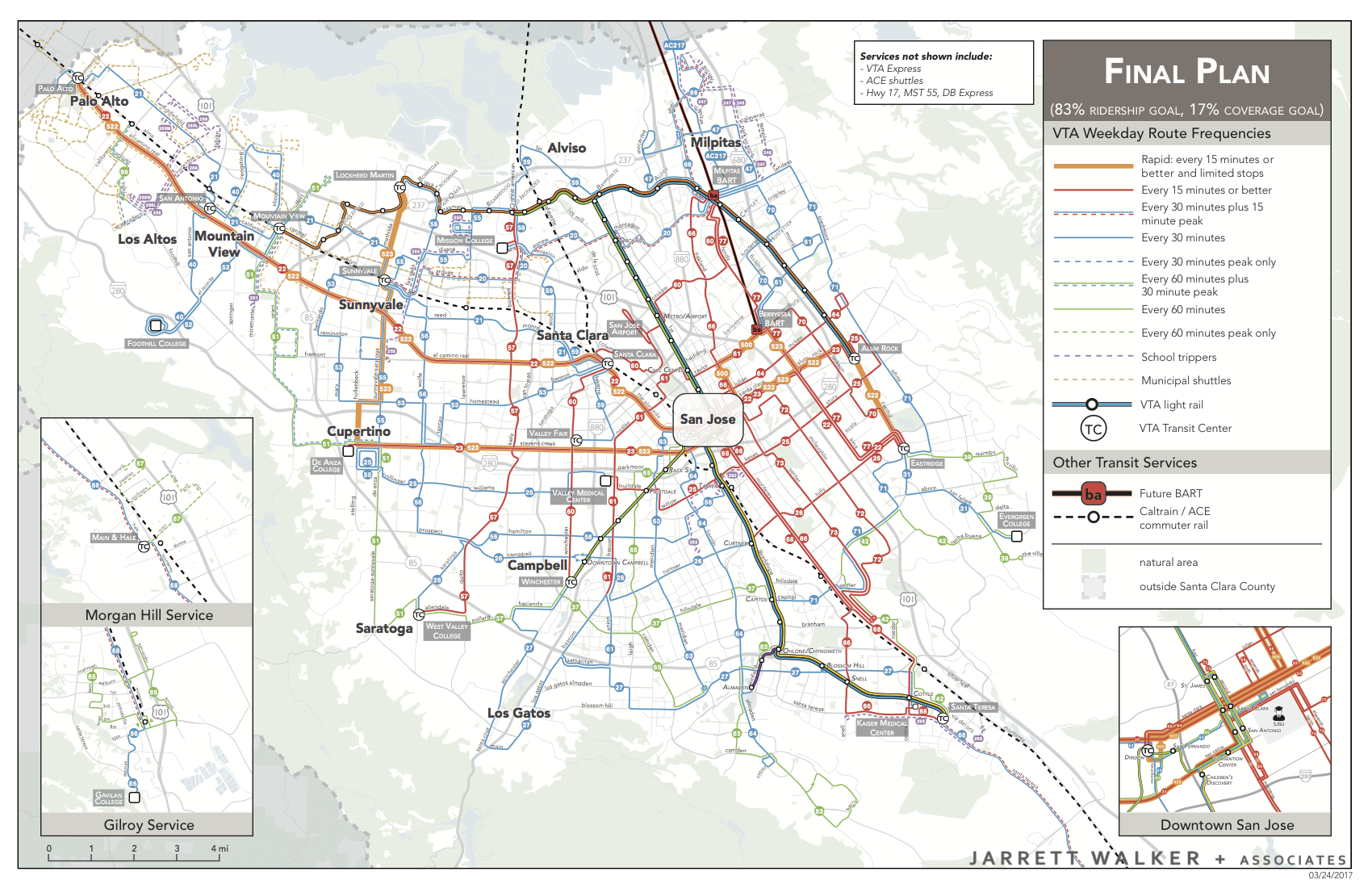

If the test for Federal funding is that a facility is used for interstate travel, fine, but this suggests a coherent interstate network of roads and rails scaled for the interstate demand only. Then, all additional capacity and upgrades needed for travel within a state would be state and local costs. What would this mean?

- The Federal government would invest to create a robust interstate road network sized to interstate needs only. In urban areas, the Federal government would fund only as many lanes as are justified by cars and trucks originating outside the state. That means two lanes at most, and it means that many Federally funded highways would have no Federal role at all.

- The Federal role in airports and maritime transportation would be viewed the same way.

- The Federal government would also fund interstate rail (passenger and freight) to the degree that this is a better investment than roads for serving interstate needs. Interstate high speed rail improvements would be squarely Federal.

- Finally, many US metro areas span state lines, so a large part of the costs of urban transit in those cities would be Federal, as it would count as interstate transportation.

Nobody would propose this policy, but only for the boring reason that it’s biased toward multi-state metro areas: The Northeast wins big while California and Texas lose. But if you could control for that, this would be a coherent principle of devolution such as Dorfman seems to be advocating.

But our car-first friends never make that argument. Instead, they just handwave about how of course highways are naturally national while those other things are local. In fact, the distinction between interstate and intrastate doesn’t line up at all with distinctions among road, rail, maritime and aviation modes — either passenger or freight.

This is why you should see through these familiar arguments, and recognize them instead as sheer claims to hegemony: “We road people are superior, so of course money should be spent on us — including giving road-based services a leg up in competition with other modes.”

The former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott liked to make the same argument:

“We have no history of funding urban rail and I think it’s important that we stick to our knitting,” the Federal Opposition Leader declared. “And the Commonwealth’s knitting when it comes to funding infrastructure is roads.”

In his autobiography, Abbott wrote about how driving a car is a quintessential Australian experience, a key to the national character. He is also known for an extreme social and cultural conservatism that is toxic in inner cities. So even among those who agreed with him, Abbott’s comments were widely recognized as an expression of a cultural agenda, not an economic one. While nodding at devolution, he was really saying that road people like him are superior to those urban transit people, none of whom will ever vote for him anyway.(1)

When you see arguments like Dorfman’s, that, I’d suggest, is what you should hear. Devolution itself is a powerful idea, but we’ll never have a clear conversation about it if it’s only used to make claims of superiority.

(1) Abbott was deposed in 2015 by Malcolm Turnbull, an urban conservative from a wealthy part of Sydney. Turnbull dumped Abbott’s roads-first view, stressing instead that Federal transport investments would be multimodal. Despite its powerful rural interests and cultural identity, Australia has a strong bipartisan consensus that its national economy depends on the functioning of its cities.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8553597/NYC_POOL.jpg)