When planners develop proposals for redesigning a bus network, how do they do it? And when is it necessary?

In 20 years of doing bus network planning around the world, I’ve encountered few systems that don’t have some major obsolete features in their design. Most public transit authorities continually fix small problems in the network but have trouble fixing the big ones.

Making superficial changes to a network is like adding little bits to a house. One by one these bits make sense, but over time they can destroy the design of the house,You may also be doing these little remodels because you can’t face the fact that the foundation is rotting.

Cities change, and every 20 years or so, the bus network should be comprehensively reviewed. Such a project should really include an exercise where you study the city’s demand patterns and design a network on a “blank slate” i.e. deliberately not considering what your network does now. Such a thought process will retain the strongest features of your existing network, but will let you discover new patterns of flow that are a better fit for your system as it is today.

Network design is a process of creative thought, not just analysis. When we rethink a network, we’re doing what a scientist does as he tries to form a new theory:

1. Data Presentation. Look at all the data and try to see NEW patterns in it that the current theory/network misses. (Geographical representations of the data are crucial at this stage. The quality of your data presentation will limit the range of ideas you’ll have.)

2. Creative Thought. Form new ideas that work with those patterns. (This step is creative rather than analytic, and proceeds in unpredictable bursts of inspiration.)

3. Analysis. Test those ideas against the data. Revise or discard those that don’t fit the data well. This is the analytic step, and must not be confused or conflated with the creative step that precedes it.

4. Go to step 2 until you have something you like.

This process is important because great network design ideas solve many problems at once, just as a good scientific theory explains lots of data at once. The single most common mistake in network planning is to think about only one problem at a time, and look only for solutions to that problem. That kind of narrow thinking may be necessary to get from one day to the next, but every 20 years or so (or more often if your city is changing fast) you need to do the larger process I’ve described.

You must also control altitude. The first stage of the work must look at the entire city or service area, to be sure that you solve problems that can be solved only at that scale. Only then can you look at details. More on this here.

My preference is to do this process in an intensive professional workshop setting, similar to the design charrette process in urban design. Typically, about 15 professionals set aside 2-5 days of their time. The people need to be a mix of roving consultants like me and staff of the agency being studied, but they all commit to be open-minded, and are encouraged to think about opportunities and not just constraints.

Sometimes, when running these processes, I’ll ask everyone to name one network design idea that they’d really like to do but that they assume is politically impossible.

The point is to break out of the constraint-dominated thought process that often prevails in the daily life of transit agencies. This isn’t a comment on anyone’s creativity, but rather an observation about the daily experience of bus network planners. Bus agency staffs get very little appreciation, and lots of criticism, no matter what they do, so they tend to become risk-averse cultures. When I run a network planning workshop, my first job is to break through that, and encourage the client’s staff to welcome their own insights even if they may seem politically impossible at first glance.

Core Design Workshop in Yekaterinburg, Russia, 2015.

The workshop room has a large table where we can sit around a drawing in progress. On the table is a base map of our study area, covered with either tracing paper or clear acetate, so that we can draw and revise over and over. The walls are covered with maps of relevant data about our project. There’s also a whiteboard where anyone can sketch out ideas that aren’t ready to go on the map.

(In 2020, of course, we figured out how to do all of this online! It works much better than you’d expect.)

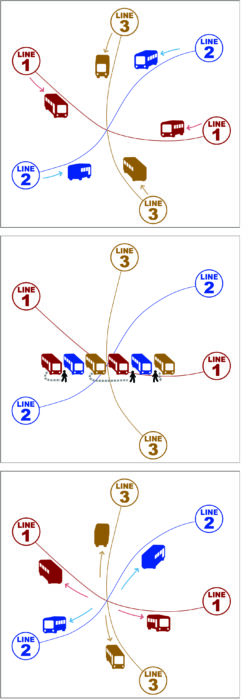

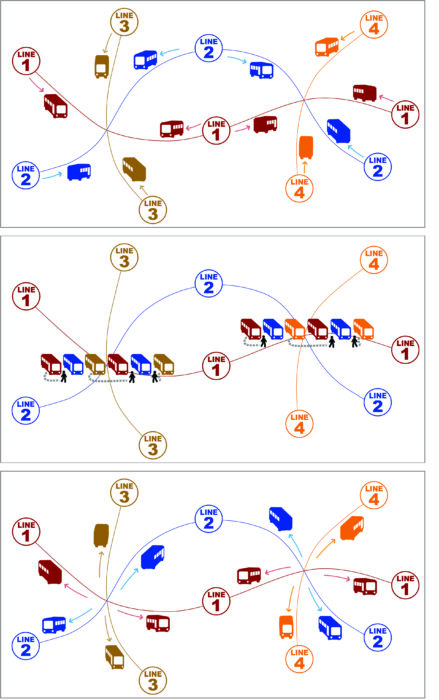

The workshop proceeds through the iterative steps that listed above. We start with a half day or day of just reviewing the data. Then we start brainstorming possible “big moves,” large structural ideas which, if pursued, would lead the rest of the network to take a new form. If we’re planning around a new rapid transit project, then that’s already the “big move.” If we’re just redesigning a bus network, we may think of big moves of our own, such as installing a grid system if that’s appropriate.

Once we have an agreement about big moves, we proceed top-down to address the more local design issues that follow from them. This sequence is important, because the big moves will have the biggest impact. The design of the Frequent Network, for example, is always a big move, and I insist that we hammer out this design before we turn to the less frequent local routes that connect to it.

As we develop ideas, we may do some quick analysis to help us verify them. We also sometimes break for field exploration, as different members of our group go out in cars to check various routings that we’re thinking of.

By the end of the workshop, we may not have total consensus, but we always have a lot more consensus than the client expected going in; we’ve always come up with ideas that were new to everyone in the room. The core workshop isn’t the end of the process, but after this point we usually have a map that bears at least a 70% resemblance to what we’ll finally recommend. More importantly, everyone in the workshop will have ownership of that process, and will see their own influence on it. This, finally, is crucial. One of the hardest jobs of a consultant is to transfer the results of his work to the client agency, so that they see the ideas as theirs rather than as “what that consultant recommended.” Ultimately, the interactive design process is the best way I’ve found of doing that.