For the last three years, Auckland, New Zealand, has been rolling out a new bus network in different parts of the city. Sunday, the final portion, the North Shore, got its new network, so the entire effort is complete. Bravo!

I worked on the original design back in 2012 (with colleagues at MRCagney‘s amazing New Zealand office) and first explained it here. While public comments have led to revisions and improvements, the most important layer, the citywide frequent network, is almost exactly what we designed.

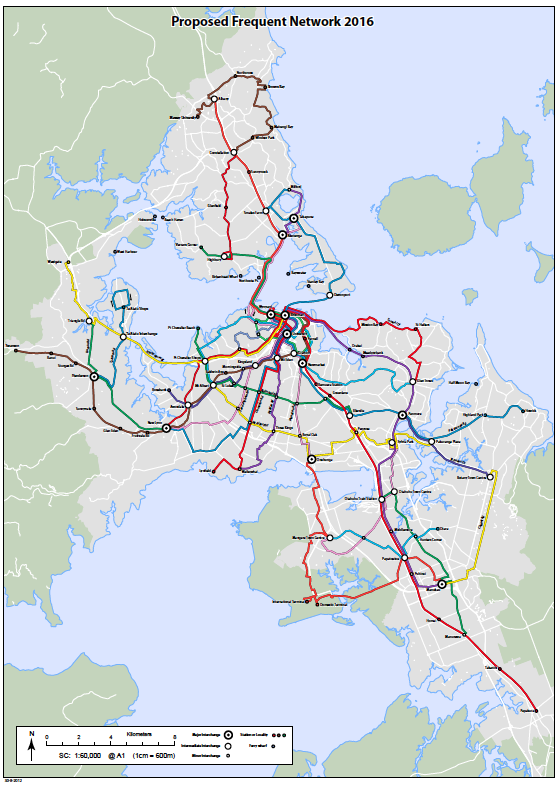

A 2011 sketch of what the all-day high-frequency network would look like when complete. (In 2011, only a tiny part of central Auckland had frequent service all day.) (MRCagney)

Even more important than the network are the principles, which Auckland Transport explains here. We figured out these principles at the beginning of the process, and they should sound familiar to anyone who knows my work. For example, this image still appears in most of my firm’s reports, showing two ways to serve an abstract city consisting of three residential areas (top) and three destination areas:

[The idea, explained fully here, is that in this simple fictional city, if you run three routes instead of nine, you can afford to run them three times as often, which means that the average wait is only 1/3 of what it was before. Even if you have to change buses in the new network, which means you make this short wait twice, you’re still waiting only 2/3 as much as you did before (1/3 at the start of your trip, and 1/3 for the connection). Hence the counterintuitive fact: a network that makes you change buses gets you there sooner. Such a network is also simpler, three routes instead of nine in this case, with buses coming so often that you don’t need at timetable.]

An important complement to the bus network redesign has been a major increase in frequency on the city’s four commuter rail lines, which enabled us to offer outlying areas frequent connections to the rail line instead of a long bus route competing with it. Now, the New Zealand government has funded a huge project to extend this network underground through the city centre, so it will function like a proper subway system.[1] This will further strengthen bus lines connecting with it and further reduce the need for lines running parallel.

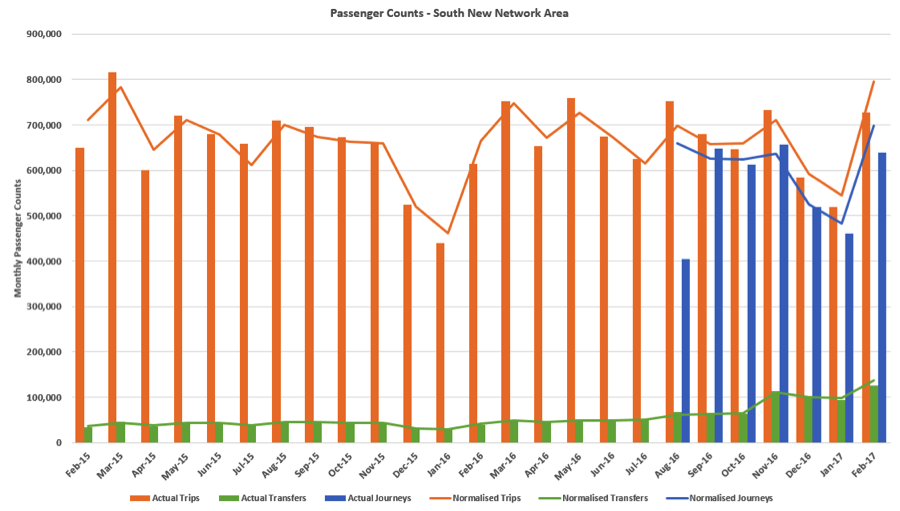

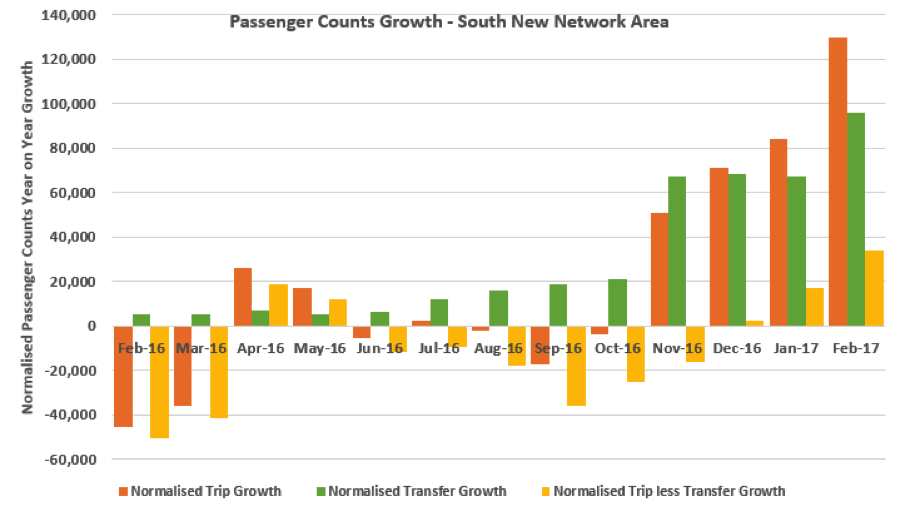

Each phase of the network has triggered gains in patronage — increases in total journeys, not just passenger boardings — so all that new frequency is clearly attracting new riders.

Many people ask me about phasing. Does a new bus network have to be implemented all at once? The answer in many cities, including Houston and Dublin, is yes: The geography of the city is so interconnected and interdependent that trying to implement a network in pieces is just too much work. The interim phase in which the network is partly new and partly old becomes a huge network design challenge in itself, as well as a challenge for communications and operations.

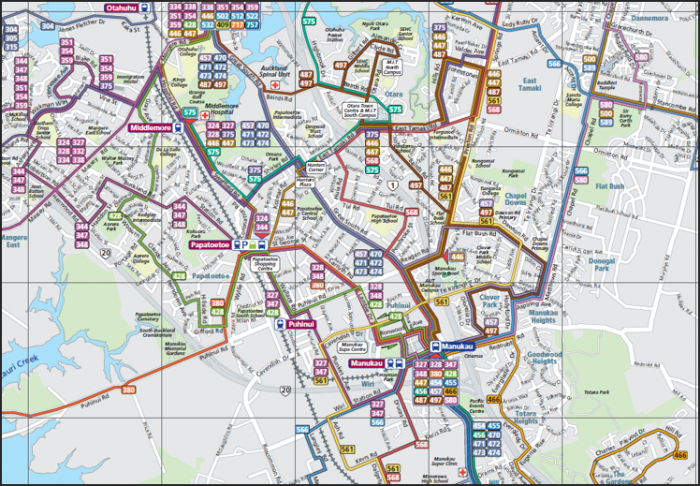

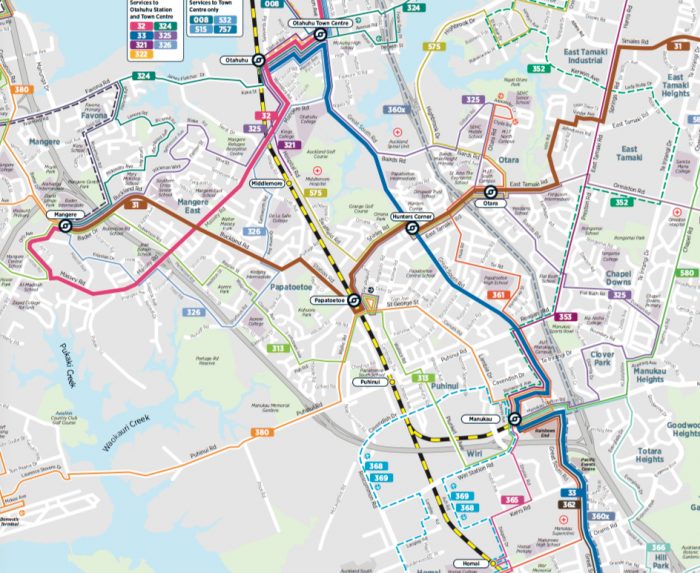

Auckland was an exception, though, because of the city’s shape. The city is so riven by bodies of water that it functions almost like an archipelago. The narrow points of connection between areas make those areas relatively easy to separate. (This is why New York City, for example, can reasonably do separate phases for Staten Island, Manhattan, and the Bronx, although Brooklyn and Queens are inseparable.)

I’ve been back to Auckland several times since the network began rolling out, and it’s great to see this great Pacific city becoming more and more oriented toward great public transport. I’ll be back there in late November, to speak at an Auckland Conversations event, and look forward to getting places sooner on the new frequent network.

Congratulations to everyone at Auckland Transport and the City for this great milestone. The plan had many important authors and advocates, but if I had to call out one it would certainly be Anthony Cross, the tireless head of bus planning who conceived this project and pushed it through, in a struggle of many years. I hope he’s happy today.

[1] North Americans are encouraged to make wistful comparisons to the eternally-deferred San Francisco Caltrain downtown extension and New York Gateway project. Further cause for antipodean triumphalism: similar projects are well-advanced in both Melbourne and Brisbane.