It's great to see the national press about the Houston METRO System Reimagining, a transformative bus network redesign that will newly connect a million people to a million jobs with service running every 15 minutes all day, with almost no increase in operating cost. Last week, when the Houston METRO Board finally adopted the plan for implementation this August, I was in New Zealand advising Auckland Transport executives on how to roll out a similar plan there, one that MRCagney and I sketched for them back in 2012. Advising on these kinds of transformations, and often facilitating the design process, is now one of the core parts of my practice.

And here is my most important piece of advice: Don't let anyone tell you this is easy.

Much of the press about the project is picking up the idea, from my previous post on the subject, that we redesigned Houston's network to create vastly more mobility without increasing operating cost — "without spending a dime," as Matt Yglesias's Vox piece today says. An unfortunate subtext of this headline could be: "Sheesh, if it's that easy, why didn't they do it years ago, and why isn't everyone doing it?"

Some cities, like Portland and Vancouver, "did it" long ago. But for those cities that haven't, the other answer is this:

Money isn't the only currency. Pain is another. These no-new-resources restructurings always involve cutting some low-ridership services to add higher-ridership ones, and these can be incredibly painful decisions for boards, civic leaders, and transit managements. Civic officials can come out looking better at the ends of these processes, because the result is a transit system that spends resources efficiently in a way that reflects the community's values. But during the process they have every reason to be horrified at the hostility and negative media they face.

If you're on a transit board, here's what these transformations mean: Beautiful, sympathetic, earnest people — and large crowds of their friends and associates — are going to stand before you in public meetings and tell you that you are destroying their lives. Some of them will be exaggerating, but some of them will be right. So do you retain low-ridership services in response to their stories, and if so, where does that stop? I'm glad I only have to ask these questions in my work, not answer them.

For a decade now I've been helping transit agencies think through how much of their service they want to devote to the goal of ridership and how much they want to devote to a competing goal that I call coverage. Ridership service should be judged on its ridership, but coverage service exists to be available. Coverage service is justified partly by the political need for everyone (every council district, member city or whatever) to have a little service, because "they pay taxes too," even if their ridership is poor. But it's also justified as a lifeline, by the severity with which small numbers of people need it.

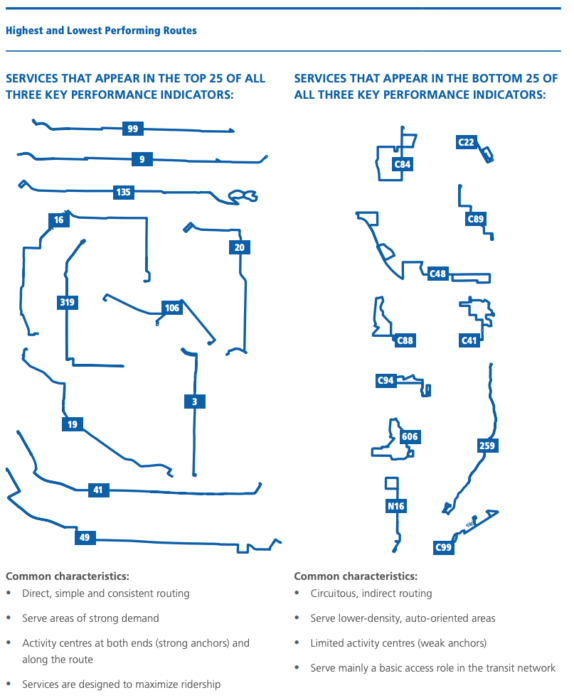

In the early stages of the Reimagining project, I facilitated a series of METRO Board and stakeholder conversations about the question: How much of your operating budget do you want to spend pursuing ridership? I estimated that only about 55-60% of existing service was where it would be if ridership were the only goal, so it wasn't surprising that the agency's ridership was stagnant. I explained that the way you increase ridership is to increase the percentage of your budget that's aimed at that goal. And if you're not expanding the total budget, that means cutting coverage service — low ridership service, but service that's absolutely essential to some people's lives.

In response to a series of scenarios, the Board told us to design a scenario where 80% of the budget would be devoted to ridership. That meant, of course, that in a plan with no new resources, we'd have to cut low-ridership coverage service by around 50%. Mostly we did that not by abandoning people but certainly by inconveniencing some of them. But there was no getting around the fact that some areas — areas that are just geometrically unsuited to high-ridership transit — were going to be losers.

We didn't sugarcoat that. I always emphasize, from the start of each project, how politically painful coverage cuts will be. The stakeholder committee for the project actually had to do an exercise that quantified the shift of resources from low-ridership areas to high-ridership ones — which was also a matter of shifting from depopulating neighborhoods to growing ones. They and the Board could see on the map exactly where the impacted people were.

And exactly as everyone predicted, when the plan went public, those people were furious. Beyond furious. There really isn't a word for some of the feelings that came out.

Houston had it much worse than most cities, for some local reasons. Along the northeast edge of inner Houston, for example, are some neighborhoods where the population has been shrinking for years. They aren't like the typical abandoned American inner cities of the late 20th century, where at least there is still a good street grid that can be rebuilt upon. In the northeast we were looking at essentially rural infrastructure, with no sidewalks and often not even a safe place to walk or stand by the road. Many homes are isolated in maze-like subdivisions that take a long time for a bus, or pedestrian, to get into and out of. And as the population is falling, the area is becoming more rural every year.

I feel the rage of anyone who is trapped in these inaccessible places without a car. I also share their desire to love where they live, and hope my description hasn't offended them. But I can't change the geometric facts that make high-ridership transit impossible there, nor can I change the reality of their declining population. And that means I can't protect civic leaders, elected officials, and transit managements from the consequences of any decision to increase the focus on ridership. Increasing your transit agency's focus on ridership, without growing your budget, means facing rage from people in low-ridership areas, who will continue to be part of your community.

Houston's situation is worse than most; less sprawling cities can generally prevent any part of the city from depopulating in the context of overall growth. But in any city there are going to be less fortunate areas, and the disastrous trend called the "suburbanization of poverty" means that increasing numbers of vulnerable people are forced to live in places that are geometrically hostile to high-ridership transit, and thus demand low-ridership coverage service.

So don't let anyone say this was easy. What's more, in Houston it was easier for me than for anyone else involved, which is why I'm uncomfortable when Twitterers give me too much credit. I flew in from afar, facilitated key workshops for the Board and stakeholders, led the core network design process, and got to go home. It was the the Board, the management, the key stakeholders and the local consultants led by TEI who had to face the anger and try to find ways to ease the hurting.

Was it worthwhile? I was very touched by what METRO's head of planning, Kurt Luhrsen, wrote after the Board's decision.

I am overjoyed for the citizens of Houston. Particularly those who are dependent upon the bus and have been riding METRO for years. Their trips to the grocery store, the doctor’s offices, work, school, church, etc. take way too long and are usually way more complicated than they need to be.

Today, with this Board vote, Houston took a giant step toward making these citizens’ lives better. That simple fact, making people’s lives better, is why I love my job in transit. It is where I draw my inspiration and today definitely recharged my batteries a bit. I am also very proud of our Board, METRO employees, our consultants, our regional stakeholders and many others who worked tirelessly to make this action today possible. These types of projects are difficult, that’s why so few transit agencies really want to do them. But today we did it. This plan will improve people’s lives, and I am so thankful that I got to play even a small role in it.

I, too, am thankful for my small role in guiding the policy and design phases of the process. I listed, here, some of the key people who really drove the process, all of whom worked much harder than I, and who faced much more ferocious public feedback than I did, to bring the plan to success.

Transit in Houston is about to become a completely different thing, vastly more useful to vastly more people's lives. But don't let anyone imply this was easy. It was brutally hard, especially for the Board and staff. Nobody would have done it if it didn't have to be done.