They were red! They made fewer stops! It was so cool! (c. 2005)

When they were first rolled out around 2000, the Los Angeles Metro Rapid lines were the hottest thing, so hot that a famous system of branding (Rapid buses red, local buses orange) was developed around them. Rapid buses run long distances along major boulevards, stopping every half mile, while local buses run alongside them stopping every two blocks. I too was a booster of the idea at the time, and soon “rapid bus” products were appearing in many cities.

But of course, the branding distinction was about speed, which all motorists understand, as opposed to frequency, which they often don’t.

The first two Rapid lines (Wilshire and Ventura Blvds) had all kinds of great features. There were architecturally designed shelters, and the City of Los Angeles helped with signal priority. Then, however, the forces of envy set in. Rapids made sense only where:

- the agency could afford very high frequency (generally no worse than 10 minutes) on both Rapid and local buses, so that it was worth waiting for the Rapid even if the local came first, AND

- corridors were extremely long with long average trip distances, because you have to be going some distance for the speed advantage of a Rapid to be worth any added walking or waiting that a Rapid would require.

But once the first two Rapids succeeded, there came the cries of “why does their street get this cool thing and mine doesn’t?”. And while the two points above were good answers to that question on many streets, LA Metro was pressured to roll out Rapid lines all over the region, in places where they made sense and places where they didn’t. Some, like Soto St, were just too short for the speed difference to be valuable to many people. Others didn’t have the frequency needed for their speed to be useful, with some coming as infrequently as every 30 minutes all day. Most of them had nothing like the signal priority of the initial two, nor the distinctive shelters. The buses were red, though, so it looked like some cool thing had been spread across the region. (For more on this political dynamic, which I call the Fishing Pier Problem, see here.)

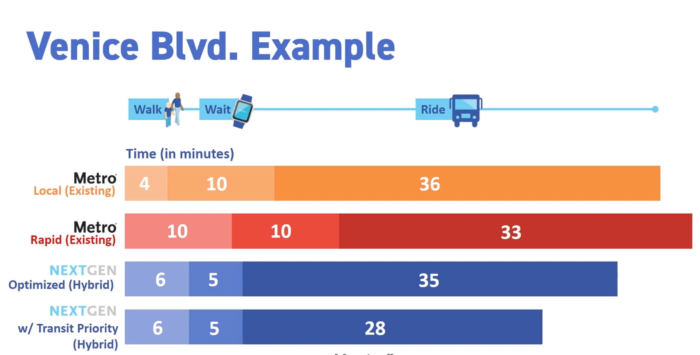

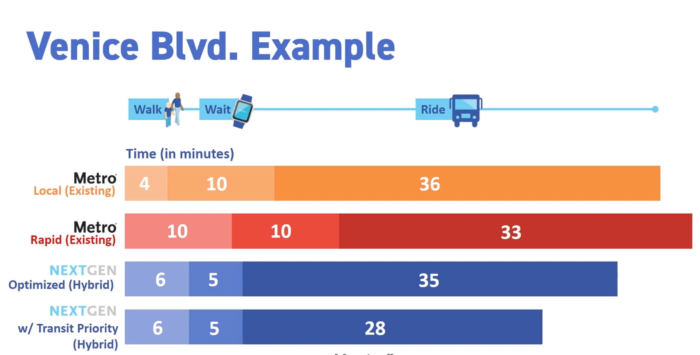

So the result was outcomes like this:

Source: LA Metro NextGen Visual Workshop (for a trip of seven miles)

If you’re on Venice Blvd but between Rapid stops, as in this example, you could walk less and use a local bus or walk further and use a Rapid. As this shows, the difference in travel time isn’t enough for that to make sense. The Rapid is only three minutes faster for that distance, but you’ll spend six more minutes walking.

The upper blue bar shows that by combining the Rapid and local buses into a single line that runs twice as often (with fewer stops than the local but far more than the Rapid) the result is a shorter total trip, because of the shorter wait. In this case, the customer walks six minutes to a single line instead of four (because the local stops are a little further apart) but then waits half as often (because the two lines are combined) and rides a trip that’s a little bit faster than the current local (again, because local stops are a little further apart). It turns out that lots of people along these long boulevards are in this situation.

Combining Rapids and local into a single more feequent line is one of the key recommendations of the newly proposed Los Angeles metro bus network redesign, the work of our respected competitor Transportation Management & Design (TMD) working with Cambridge Systematics. Russ Chisholm of TMD, whom I used to collaborate, actually led the planning that created the Rapids in the late 1990s, so it’s fitting that he’s also gotten to plan for their obsolescence.

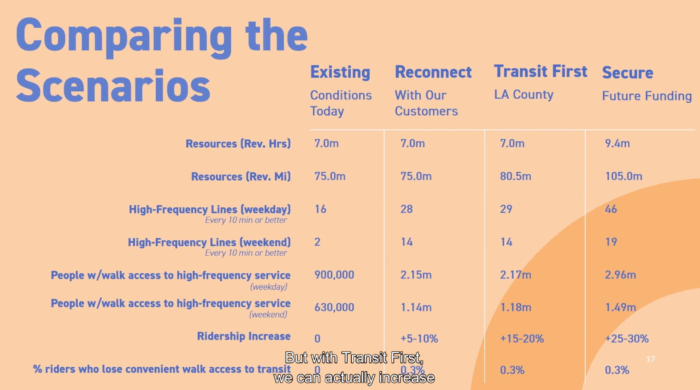

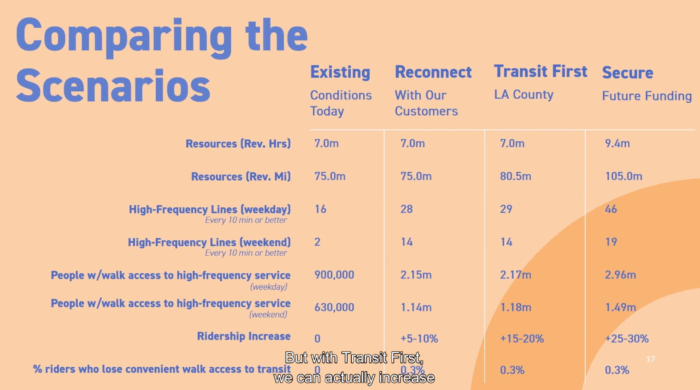

Here are the outcomes. (“Reconnect with our customers” is the no-growth redesign, the plan that reallocates existing service instead of adding new service. “Transit First” adds bus lanes and other infrastructure, for even more improvement without adding operating cost.)

Source: LA Metro NextGen “Virtual Workshop”

The vast increase in the number of people with access to frequent service, from 900,000 to 2.15 million, is the key to why this plan is likely to succeed. A huge share of this outcome results from combining the Rapid and local services into single lines, since many streets that formerly had both a local and a Rapid every 15 minutes will now have a bus every 7.5 minutes or so.

As always, a redesign that doesn’t add more service involves cutting some unproductive service, but here only 0.3% of riders losing walk access to transit, which is also impressive. These are the least transit-oriented places in the region. Still, we can expect ferocious complaints. It may seem like 0.3% of the ridership isn’t much, but they and everyone they know, with some public relations skill, can make it sound like the plan is a disaster. Even if nobody were losing their service, some people will be angry when you change anything. So if you live in Los Angeles, it’s important that you engage with the plan!

That brings me to my main critique. In exploring the website, I found the plan difficult to learn about. There’s no shortage of materials selling the plan to me, and there’s no shortage of route-by-route details, but I wish there had been a report that makes the argument for the plan and explains the thought process that led to its design. (No, PowerPoint slide decks are not reports, because they don’t show the logical relationships between ideas; they are useful only with narrating voice attached.) The plan’s data viewer is pretty good, especially the tool that helps people see how the plan changes where they go. We do similar things on our projects and they should be standard procedure now.

But I can’t find much on the website that seems to be speaking to non-riders, including anyone who cares about outcomes that the plan improves (congestion, climate, urban redevelopment, access to opportunity, social justice etc etc). If you might support the plan for any of those reasons, the comment survey (a tab within the data viewer) will frustrate you. It assumes that you’re evaluating the plan only selfishly, in terms of whether it will improve your travel. (This also discourages feedback from non-riders who could see other selfish benefits, such as a business that gets better access from potential customers and employers, or a benefit for a friend or relative.) Getting these plans across the line requires selling a big picture to the biggest possible audience, especially given that some angry riders will be yelling. I hope that, in some forum that I can’t find on the website, that pitch is being made.

I wish LA Metro the best with this redesign. It looks great. It presents huge opportunities for better access to opportunity, more sustainable urban form, climate benefits, reduced local emissions, and safety. It deserves to be allowed to succeed.

Public transit in the US is facing an unprecedented crisis. Fare revenue will collapse as people stay home, while the tax revenues that transit relies on will also decline steeply as we go into a recession. Some small transit agencies are shutting down, but most are trying to keep going, as a public service. As I recommended, many are cutting peak commute service but keeping the all-day service that is a city’s lifeblood, and the lifeline of the people who are keeping things running right now.

Public transit in the US is facing an unprecedented crisis. Fare revenue will collapse as people stay home, while the tax revenues that transit relies on will also decline steeply as we go into a recession. Some small transit agencies are shutting down, but most are trying to keep going, as a public service. As I recommended, many are cutting peak commute service but keeping the all-day service that is a city’s lifeblood, and the lifeline of the people who are keeping things running right now.