The next webinar about the new edition of my book is tomorrow, September 12, 2024, sponsored by ITE Toronto. Of course, you can join from anywhere in the world, but the Q&A will probably be Toronto-focused. I’ll be introducing the new edition of my book and talking about some new ways to think about public transit planning. Please register in advance!

The next webinar about the new edition of my book is tomorrow, September 12, 2024, sponsored by ITE Toronto. Of course, you can join from anywhere in the world, but the Q&A will probably be Toronto-focused. I’ll be introducing the new edition of my book and talking about some new ways to think about public transit planning. Please register in advance!

Interview on BBC Northern Ireland

Following up on this post about the Northern Ireland public transport situation, I was interviewed recently by John Campbell as part of a BBC program on the topic. I’m right at the beginning, and my part runs for about 10 minutes. Hope you enjoy. It’s here.

Following up on this post about the Northern Ireland public transport situation, I was interviewed recently by John Campbell as part of a BBC program on the topic. I’m right at the beginning, and my part runs for about 10 minutes. Hope you enjoy. It’s here.

We’re Hiring!

We have openings at or near entry-level in our Portland, OR and Arlington, VA offices! Applications close Sept. 27. See here.

Northern Ireland: A Vision for Better Buses

We really enjoyed our work, in collaboration with Aecom, on the new bus planning document for Northern Ireland public transport operator Translink.* It aims to inform future policies, strategies and plans with respect to land use and transport planning. It’s called Bus Better Connected. The short and graphically rich report can be downloaded here.

Our role was mostly in Chapter 3, which lays out some of the choices that leaders will have to face in taking the next steps on public transport. For years, Translink has been pushed in opposite directions. They have been expected to attract patronage (which is tied to both financial and climate/sustainability goals) but they are also expected to serve everyone’s needs, including in rural areas where demand will always be low and service will be most expensive to provide. This is the patronage-coverage tradeoff, and much of our work in the report goes into explaining it and its consequences. (I did the first academic paper on this topic back in 2008; it’s here.)

There are some unusual twists in Northern Ireland’s case. For example, parents are entitled to send their children to distant schools, and Translink is expected to get them there no matter how expensive the resulting services are. Sooner or later, Northern Ireland’s government will have to think about their priorities for public transport, and give Translink a more realistic definition of success.

Of course, one way out of this problem is to fund more service, as the rest of the island is doing. In the course of the network designs we’ve done across the Republic of Ireland for its National Transport Authority, we’ve been instructed to increase the total quantity of service dramatically, ranging from over 30% growth in Dublin to over 70% in Waterford. Our conversations in Northern Ireland suggest that nobody there knows where the money would come from to do this. But if climate and sustainability goals truly have the force of law, as they do — and if nobody wants to reduce rural services — then the current level of public transport will have to increase. There’s no other way the math works.

What’s next? Our contracted work in Northern Ireland is complete, but we hope to be involved in helping frame future conversations that can lead to a public transport network that meets Northern Ireland’s goals.

*I have now done work for three agencies called Translink, in Vancouver, Belfast, and Brisbane!

San Antonio Welcomes New Map with a Splash

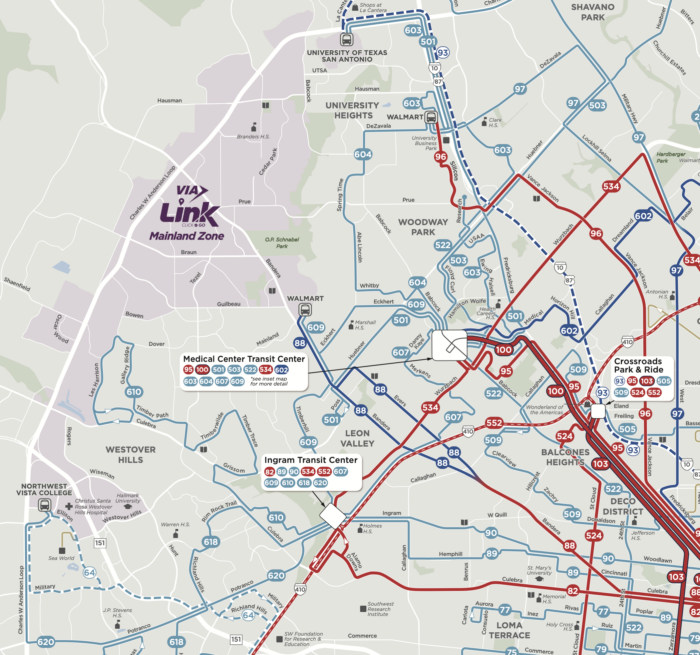

Source: Landing page for new system map at website of Via in San Antonio, at https://www.viainfo.net/newmaps/

For a couple of years now, our firm, which is mostly known for transit planning consulting, has also been making network maps for transit agencies. Not “interactive maps,” which invite you to chase flickering, vanishing content around a little screen, but good old physical maps — the kind you can post in a bus shelter, or on your wall. Like most of what we do, there’s an advocacy angle: Even in the age of trip planners, we really believe in static maps. They help people see the structure of the network and how it works with the structure of the city. They invite exploration. And they are especially useful for educating all the decision-makers in the community who do things that affect public transit, like deciding where important destinations will be located.

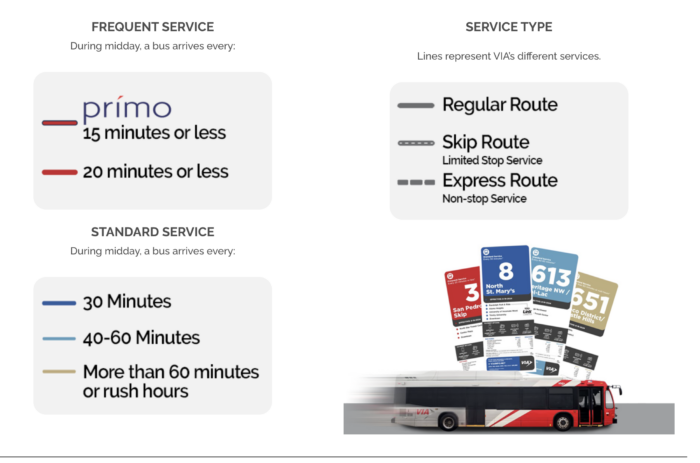

So we’re really excited that our map for San Antonio’s transit agency Via is not just published, but published with a splash, welcoming everyone to “the new colors of the city.” Those colors, of course, are our firm’s usual way of showing frequency clearly. Hot colors for high frequency, because those catch the eye, and cooler colors for lower frequency. A slightly darker red signals the Bus Rapid Transit service, locally called Prímo.

Finally, here’s a bit of the map, but you can download the whole thing here.

Those dark red lines are the frequent network, where service is always coming soon. Want to build something that will need transit? Build it on those red lines! Thinking of relocating and want transit to be good? Locate there! Sending that signal is one of many reasons that transit agencies should still have beautiful static maps, and spread them far and wide.

Ricky Angueira: A “Top 40 Under 40”

I have mixed feelings about the whole system of awards that runs through the public transit industry in the US, but it’s still nice to see real excellence rewarded. My colleague Ricky Angueira showed up on Mass Transit Magazine’s list of leading young professionals, their “Top 40 Under 40.” This award begins with a nomination from one of our clients, not from us.

I have mixed feelings about the whole system of awards that runs through the public transit industry in the US, but it’s still nice to see real excellence rewarded. My colleague Ricky Angueira showed up on Mass Transit Magazine’s list of leading young professionals, their “Top 40 Under 40.” This award begins with a nomination from one of our clients, not from us.

Since joining our Arlington, Virginia office in 2019, Ricky has become a valued project manager and service planner. He managed our recent network plans in Williamsburg, Virginia and Knoxville, Tennessee, and also led the analysis team for our complex work on service restoration priorities for San Francisco MTA in 2021. He’s become adept at all the aspects of a network plan, including navigating the local politics of each community.

Ricky also leads public-facing network maps for our clients. He managed the design and creation of maps in Miami, Boise, San Juan (Puerto Rico) and now San Antonio, and is now starting a similar project in Cambridge, UK.

Finally, as Scudder Wagg takes over as President of our firm, Ricky will be the new manager of our Arlington office. It’s great to see this recognition of one of our leading talents.

Louisville: Service Concepts for a Financial Crisis

by Scudder Wagg

Louisville, Kentucky is the largest city in Kentucky and one of the faster growing regions in the state for the last decade. On the border between North and South and on the Falls of the Ohio, Louisville has long been a crossroads of the country and a major transportation hub. Today it is the home of a major UPS hub and has a burgeoning tourist industry focused on the local spirit: bourbon. Since 1974, Jefferson County (now merged into Metro Louisville city) has had a dedicated funding source for transit, to support the regional agency: Transit Authority of River City (TARC).

Unlike other communities that have sprawled significantly, Louisville maintains a busy and dense downtown with its main community college campus and two major medical centers in the larger downtown area. Yet, while the region has grown significantly in the last 30 years, it has grown more horizontally than vertically in that time. This has created a long-term challenge for TARC: its service area has grown horizontally faster than its financial capacity has grown. This long-term trend led TARC into a challenging situation even before the pandemic. Its operating costs were exceeding its operating revenues, so it had a structural operating deficit for a decade before the pandemic. During the pandemic, federal funding helped TARC fill the structure deficit and mostly maintain its network. Now, like many agencies, TARC is approaching a “fiscal cliff” as Covid relief funds run out, operating costs go up due to the difficulty of hiring workers, and pre-pandemic fare revenue aren’t returning.

Without additional revenue, TARC is facing the possibility of cutting service levels by 50% relative to the Spring 2024 Network. TARC has already started cutting service, dropping back its weekday service to Saturday schedule of service on many routes as of June 30. But these cuts are modest compared to what’s coming if new funding can’t be found.

Our firm is helping TARC and its partners around the region consider how the transit network can change under these circumstances. TARC doesn’t want to shrink, and we certainly don’t envy their situation, but TARC has no authority to raise revenue on its own. So, the best that we and TARC can do is to clearly show what’s possible and ask the community and its leaders to tell us what they prefer.

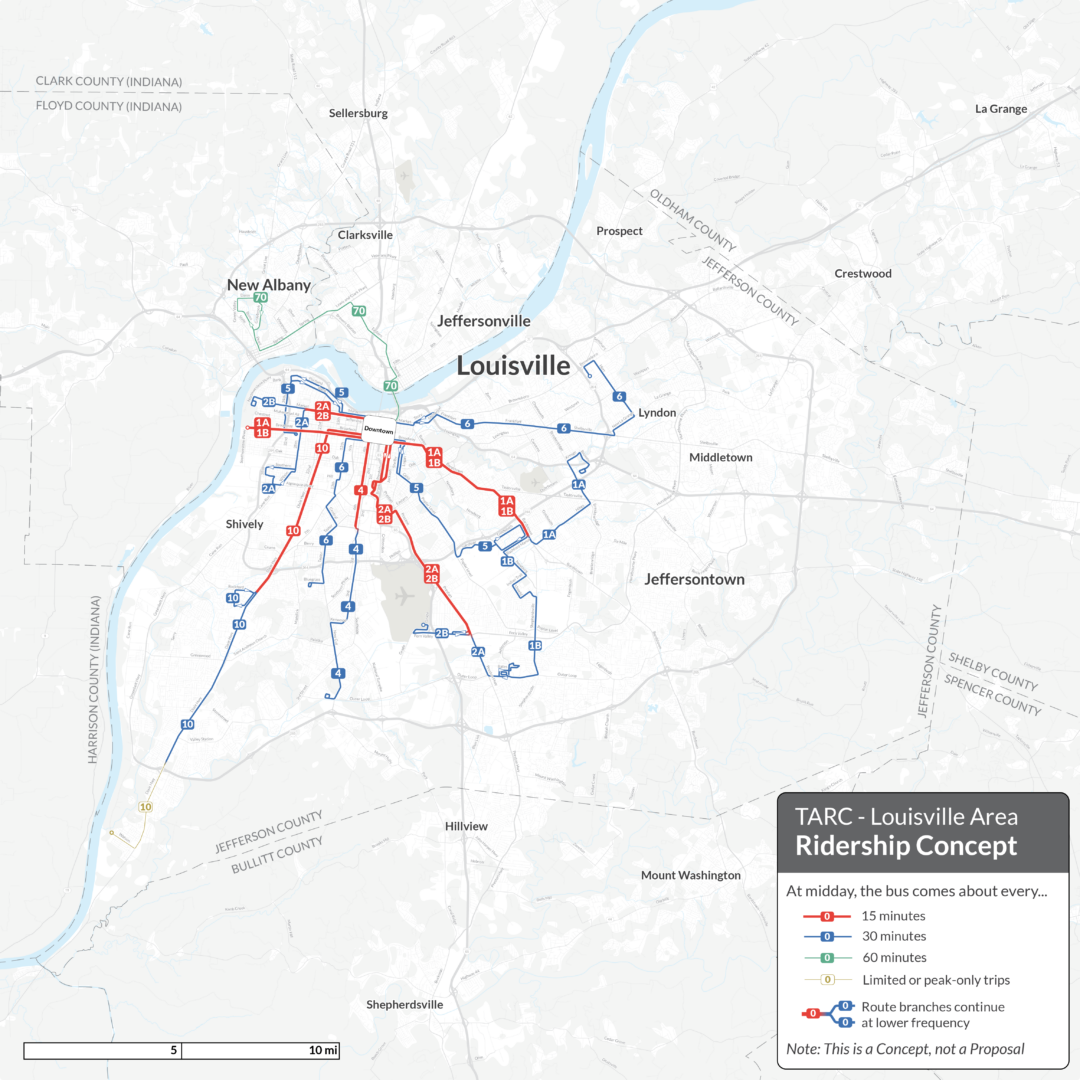

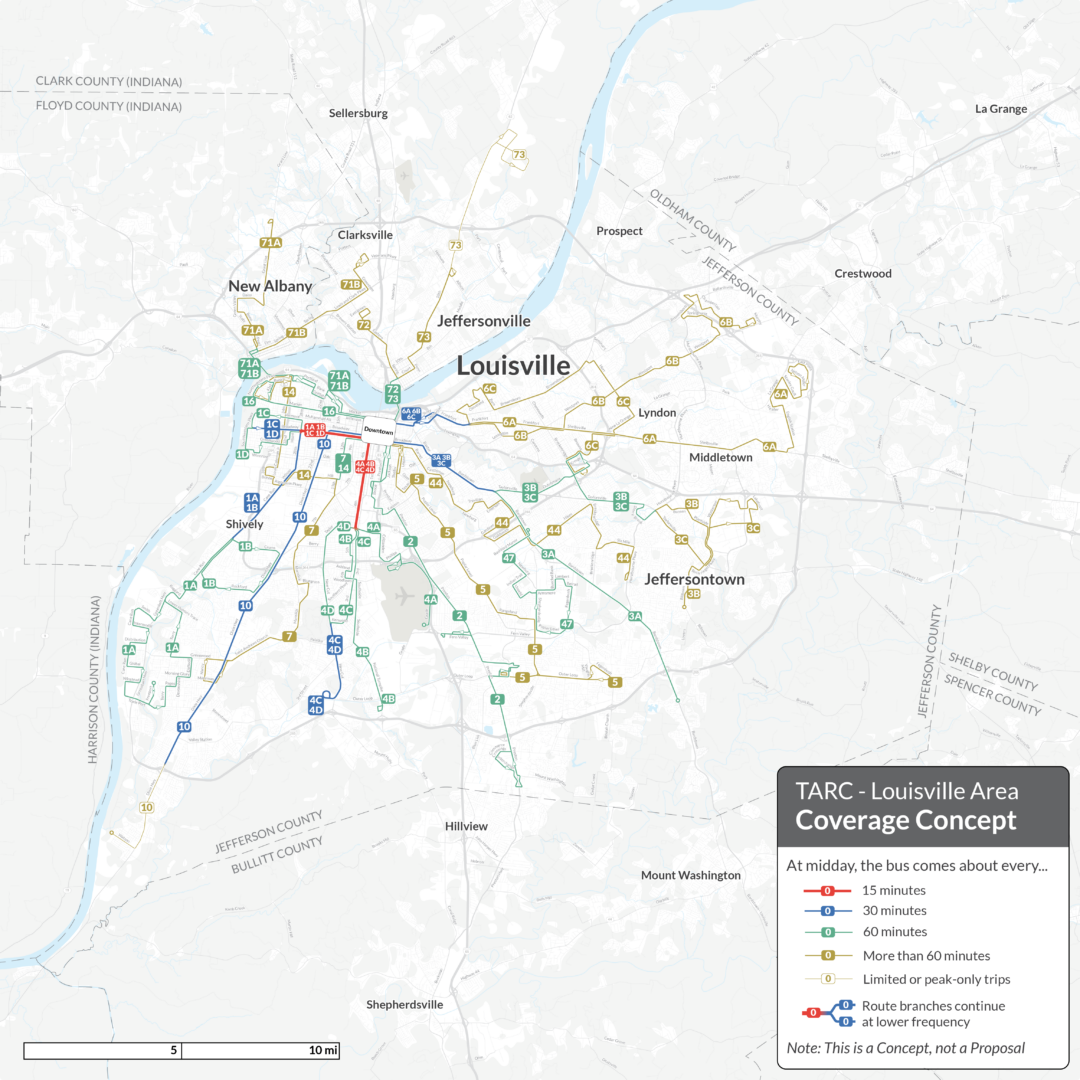

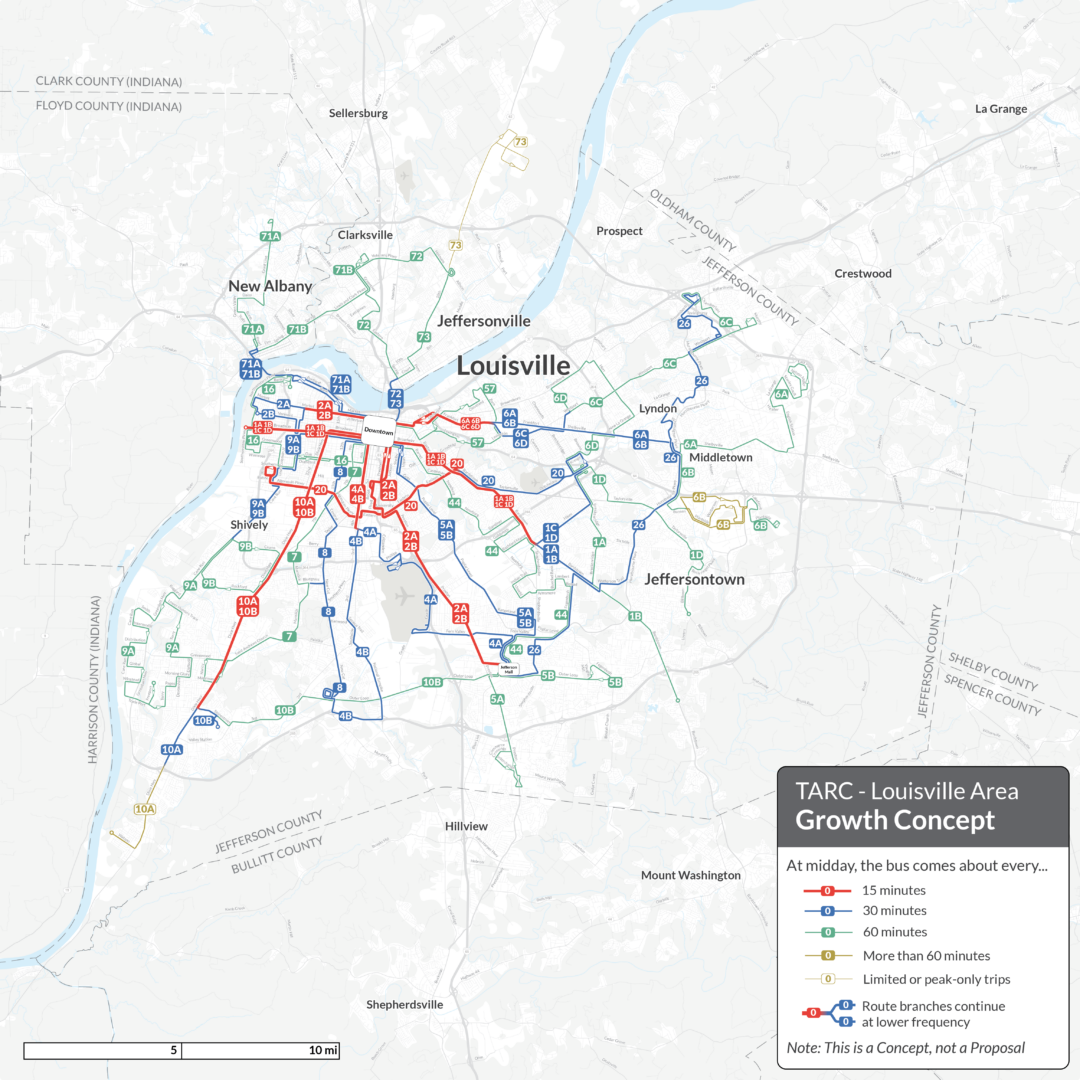

To clarify what’s possible we have drawn three concepts to show what a future TARC network would look like. Two of those concepts are constrained to the projected revenues and require a 50% cut in service. The third, the Growth Concept, shows what could be achieved with a redesigned network and additional investment that allows TARC to grow service by 12%.

Ridership and Coverage Concepts if There Are No New Revenues

If TARC does not receive additional funding, it will have to cut service 50%. This will require a difficult tradeoff between competing goals of ridership and coverage. To illustrate this, we’ve provided two network concepts:

- The Ridership Concept focuses on providing frequent service on the areas that are more likely to use transit – where there are more people and more jobs. It keeps service focused on frequent corridors in the densest, busiest parts of Louisville, but also covers a much smaller area than today’s network. By keeping 15-minute and 30-minute service near most existing riders, this network would maintain reasonable access for most users of the existing system, and therefore maintain ridership to the maximum extent. However, some existing riders are in the low-ridership area, and they would have no service.

- The Coverage Concept focuses on maintaining the existing amount of coverage and provides some level of transit service – although at greatly reduced levels – to most of the area. Nearly all routes in the network would be hourly or worse in this network, so far fewer people would find service useful. Therefore, many existing riders would likely try to find alternatives, and few people would choose to ride this network.

As always, these are two ends of a spectrum, and not an either-or choice.

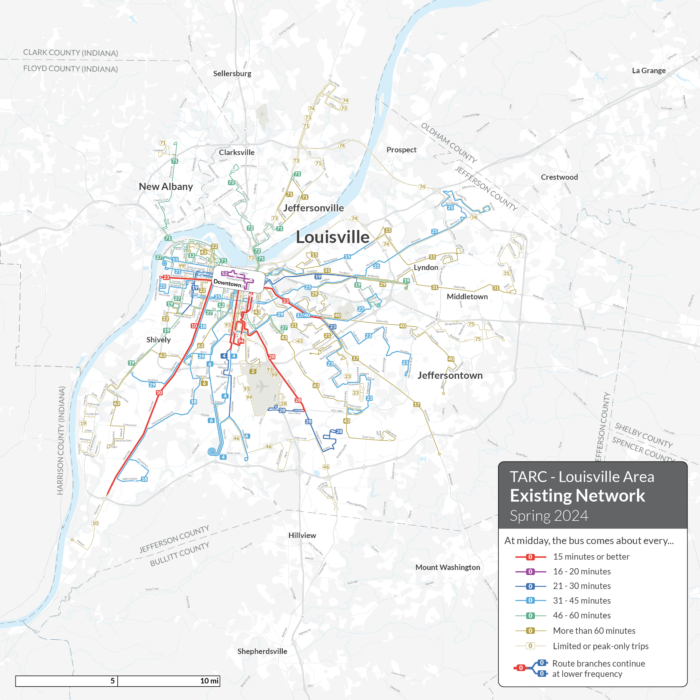

When looking at the maps, be sure to notice the colors, which indicate all-day frequency. Red means service every 15 minutes all day. The frequency colors are explained in the legend.

Here is a map of the Spring 2024 network (the one we are treating as existing for the purpose of our analysis) and maps of the two constrained Concepts.

The system as it was in Spring 2024, which we are treating as the baseline although some changes have happened since then.

Ridership Concept: If there are no new revenues and TARC must take a 50% service cut, here is what would be left if the goal were ridership. This concept deletes all service where ridership potential is low due to the development pattern, while protecting frequencies in the dense and walkable areas where ridership potential is highest.

Coverage Concept: If there are no new revenues and TARC must take a 50% service cut, here is what would be left if the predominant goal were coverage. The Coverage concept retains service almost everywhere but at the cost of much worse frequencies.

Growth Concept: New Revenues

The Growth Concept shows what TARC could look like if the community can find additional funding to grow service levels and is willing to accept a big change in the network. It maximizes service in areas of high ridership potential and maintains most of the existing coverage. It also adds features to the network, like more cross-city connections, suburban transit hubs, and new routes in growing areas. This concept shows what Louisville transit would look like if TARC prioritized meeting more of the unmet transit needs of the community and could invest to position the system for future growth.

The Growth Concept shows what could be achieved with a 12% growth in service, as opposed to a 50% cut. This would require substantial additional funding for transit service, but would keep service at a level typical for comparable US cities.

The online survey is out now, and TARC staff and the project engagement team will be seeking in-person input at several events through August and September.

We often frame transit conversations around a ridership-coverage trade-off, instead of starting with recommendations. That framework is particularly relevant in this challenging and unprecedented situation for TARC. No one in Louisville has had to imagine such a massive change for transit as a potential 50% cut in service in the past, so it demands a complete shake up of the network to do the best that’s possible within the resources available. Of course, what’s best depends on the community’s priorities, which is precisely why these concepts can help everyone think clearly about their own goals for transit in Louisville.

If you know anyone in the Louisville region, send them to the project website so that they can explore further and provide their input on the Concepts. We also encourage people to read the our two reports (Existing Conditions and Concepts Reports) that detail existing conditions, these Concepts, and the outcomes of the conceptual service changes and the choices that shape transit networks.

Scudder Wagg is President of Jarrett Walker & Associates and is the Project Manager of our Louisville work.

A Presidential Transition

On August 1, 2024, I will cease to be the President of Jarrett Walker + Associates. I founded the firm and hired its current senior managers, but now it’s time for me to step back. Scudder Wagg, who has led our Arlington, Virginia office since its inception six years ago, will be our new President.

Our clients and collaborators probably won’t notice a big difference. The eight owners of the firm are also the senior staff, so the senior team that reports to the President is also the Board to which the President reports. We also take pride in having no external owners or investors looking over our shoulders. All this means that even as President I’ve been more of a coordinator, making big decisions only once it was clear that we had a consensus.

But Scudder is a better manager than I am, so I’m sure many things will improve. Over the last few years, people have occasionally asked me if I would apply for various CEO positions as they came open at public transit agencies. I was flattered, but I know that management isn’t my strength. I don’t really like being in power. I don’t like how people behave toward me when they see me as a power figure. I’d rather be the advisor than the executive.

So now I’ll get to do that. I will continue to be the lead planner on our biggest network design projects, and I’ll continue to teach and write. I am 62 now and expect to continue working part time for at least several more years. I look forward to many more great collaborations, and to spending less time thinking about management. Scudder will do a great job.

How to Subscribe to this Blog

Some people like to get this blog’s new posts by email. Here’s how.

On the black bar in the banner at the top of the blog, click this symbol:

Enter your email address and click “Subscribe”.

Easy! Thanks for reading!

Chicago Area: Rethinking Both Pace and CTA

As the State of Illinois launches a complex conversation about how to fund public transit into the future, our firm has been doing planning work with two of the three big agencies in the Chicagoland region: Chicago Transit Authority (CTA), which mainly covers Chicago, and Pace, which covers almost all Chicago suburbs. I thought it would be a good time to share thoughts from both of those projects.

Recently, I listened to a big State Senate Transportation Committee hearing in which all of the agency heads in the region spoke. The key issues facing the region are:

- a “fiscal cliff” which threatens all the agencies in 2026, as Covid relief funds run out, operating costs go up due to the difficulty of hiring workers, and yet pre-pandemic fare revenue can’t be expected to return.

- a proposal to consolidate the three agencies (Pace, CTA, and the regional rail agency Metra) into one giant agency, supposedly to save money or achieve efficiencies.

To help with these debates, I want to lay out my view here why the agencies need more funding, and why I think consolidation would be a bad idea.

Why the CTA Needs More Money

We just completed a Framing Report for Chicago Transit Authority’s Bus Vision Project. We put a big effort into this report because we wanted to create a sample of all the things we could do, especially in access analysis, to illustrate exactly how a transit system functions and how it addresses various goals.

The report took a long time to write and was somewhat overtaken by events: You’ll notice that it mostly describes the 2019 network, and then more briefly describes what’s happened since then. As CTA recovers from the pandemic-related hiring crisis, the 2019 network is not exactly what it should go back to, but it still represents the most recent “non-crisis” state of the network, so it’s a good point of reference.

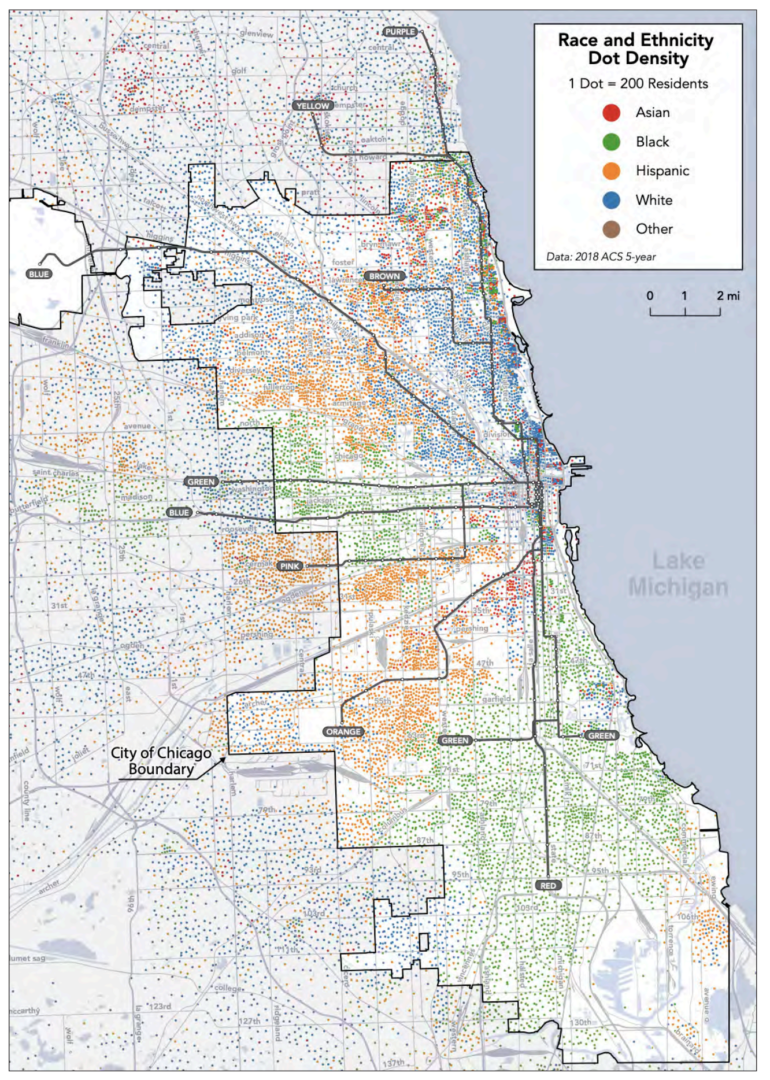

The report’s most important point is that Chicago’s geography creates a tradeoff between the goal of ridership and the goal of equity, because Chicago has a large low-income and racial minority population living in especially remote parts of the city, often at low densities or in areas with other physical barriers to service, where service to them is expensive per person to provide. This geography has a history of course, often tied to racist policies and practices that were common in the past.

The racial geography of Chicago and its inner suburbs, from our report. White people (blue) live mostly around downtown or in the northern third of the city, where density is high and travel distances are short. The rest of the city features “pie slices” of mostly Hispanic/Latino (orange) or mostly Black (green) areas. Black people (green) dominate the remote South Side, where they tend to be furthest from jobs and opportunities.

The ridership-equity tradeoff is a consequence of the mathematically inevitable ridership-coverage tradeoff. A ridership-equity tradeoff arises wherever a ridership-maximizing network design would inadvertently disfavor disadvantaged groups, because those groups tend to live and travel in places where their needs are more expensive per person to serve. Chicago has this problem in a big way.

We have two key findings about this problem:

- Transit is doing a lot to help, and it can do more, but only by running some services that won’t be justifiable on purely ridership grounds.

- Transit by itself cannot be expected to heal the legacy of decades of racist land use and real estate policies. Only redevelopment that reduces the isolation of low-income and minority areas, and adds more jobs and educational opportunities near them, can do that.

This conflict between ridership and equity goals is important because CTA has long labored under an unrealistic requirement to pay 50% of its operating costs from the farebox. In 2010, funding shortfalls related to the recession led to service cuts that made it difficult to maintain equity.

A new vision of CTA will need to create a set of standards that will accurately reflect the real goals that motivate support for public transit. These will surely include an equity goal that will be a counterweight to a ridership goal, because it will justify service expansions in disadvantaged areas despite their lower ridership potential. The balance between those competing goals will need to be chosen, as a political decision. But as always when there are tradeoffs, expanded funding makes it easier to do both.

Chicago is a city with vast unrealized transit potential. Its grid geography allows for especially efficient network structure. It has many areas that could be redeveloped in more transit-oriented ways, especially to improve the balance between housing and activities on the South Side. But it is held back by two things: inadequate protection from traffic, which CTA and the City of Chicago are also working on, and inadequate frequency, which is purely a matter of operating funds.

I will be presenting to the Chicago Transit Board (which governs CTA) on this report later this year, and that will be the end of our contract. I don’t know if we’ll have any future role in CTA’s Bus Vision Project. Meanwhile, if you want to understand the CTA’s situation in more detail, please look at our report.

Why Pace Needs More Money

In the hearing, one Senator emphasized that he wanted to talk first about a vision of service, then about governance, and finally about funding. That suggests that rather than just talking about how to address the “fiscal cliff”, so as to keep things as they are, this would be a good time to present a positive vision of the level of service that could transform the relevance of public transit across the region.

That’s what we’re doing for Pace, the agency that provides bus services to almost all of the Chicago suburbs. Later this year we expect to release a report that will show both what Pace could do if its funding returns to 2019 levels, which is not much, but also what it could do with an expansion of funding. The public outreach process on those alternatives will happen toward the end of 2024.

There’s one finding I can share now, which won’t be a surprise to anyone who knows the network. Pace has never been resourced to keep up with development and population growth of the last 70 years.

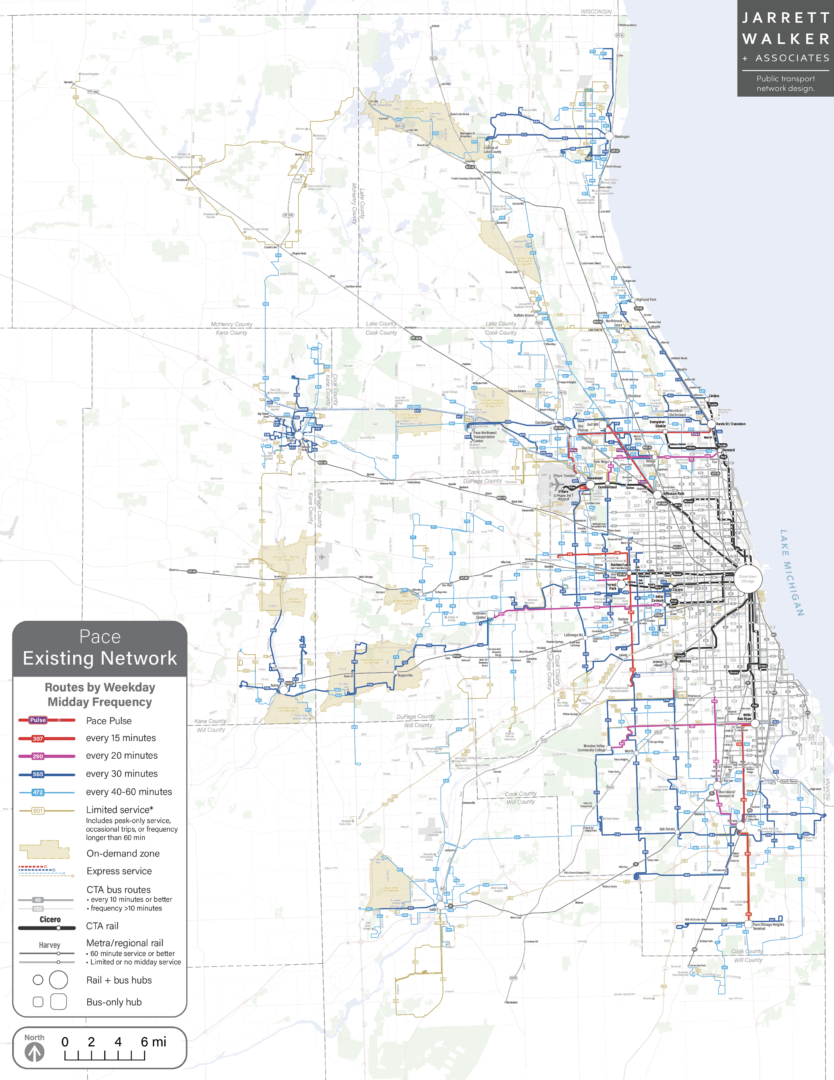

If you look at the Pace network, you’ll see intensive local services focused on places that were already built out by the mid-20th century, mostly around the edges of Chicago and in the large, old satellite cities of Waukegan, Elgin, Joliet, and Aurora. An enormous area of newer suburban development has very little service, just a thin scattering of hourly bus routes and a few rush-hour express services.

The Pace network, with red denoting high frequency. (See legend.) Service is concentrated on the edges of Chicago and in the older satellite cities, leaving large developed areas, including much of DuPage County, unserved.

So when regional leaders think about how Pace should be resourced, they have to keep in mind that for decades Pace has been unable to grow as the region has grown.

That’s why the Pace project will show two alternatives for a substantial expansion of service, which is currently unfunded. We need to show people what it would mean to plan based on needs rather than just on constraints, and how that network could transform the possibilities of life in all of the suburban cities. These scenarios would bring service up to a level that comparable suburbs in many other states already have.

Will Consolidating the Agencies Help?

As I am a consultant who sees both CTA and Pace as clients, you should not expect me to disagree with their managements in public. So of course you should expect me to share their opposition to consolidating CTA, Pace and Metra into a giant agency.

But I really do think it would be a bad idea, for the same reasons that I’d oppose similar moves to create a single giant agency for the San Francisco Bay Area, which has also been proposed.

First, there aren’t that many economies of scale that arise from consolidating agencies as large as CTA and Pace. The resulting agency would be huge, and you should expect bureaucratic inertia to increase with hugeness. Two 50-bus agencies probably have a lot of duplicated administrative functions that you could consolidate in one 100-bus agency, but at the already-huge scale of CTA and Pace, further consolidation probably won’t eliminate much administration, because the job the new agency would have to do is so vast and diverse.

More importantly, dense core cities like Chicago and San Francisco have profoundly different transit needs and transit politics than their suburbs. Many US cities that are served by regionwide transit agencies have constant conflicts with their suburbs over how to get their needs met. Transit needs per capita are higher in dense cities, yet it is often difficult to get a regional transit authority, especially one dominated by suburban cities, to apportion to the core city more than its per capita share of service.

Dense cities are also where the most can be achieved through intimate coordination of transit planning, land use planning, and street planning. Since the latter two are controlled by city government, a lot can be achieved by urban transit agencies that are close to city government, if not part of it. San Francisco already has the model of an integrated transportation agency that handles both transit and street planning, allowing those functions to be harmonized. If you were going to merge CTA with something, it might make sense to merge it with Chicago Department of Transportation. Even now, CTA is ultimately answerable to the Mayor of Chicago, just as the SFMTA ultimately answers to the Mayor of San Francisco, so the Mayor is in the position to make transit, street planning, and land use planning work together.

In the hearing, Pace Executive Director Melinda Metzger argued that a combined Chicagoland public transit agency would also be bad for the outer suburbs, because Chicago’s interests would dominate. On balance, I think both Chicago and its suburbs should fear the creation of an agency so huge that it will be hard to bring its resources to bear on the actual problems of each community.